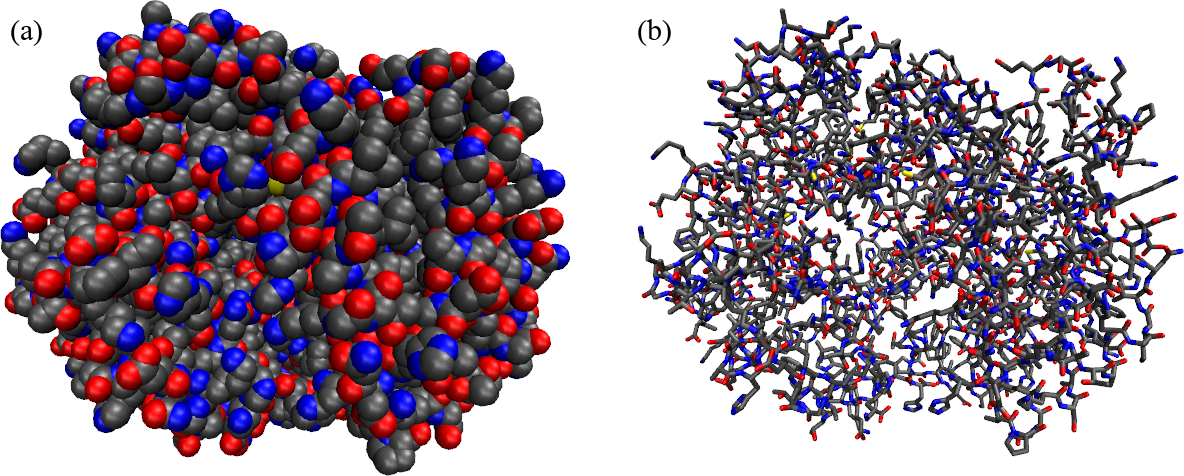

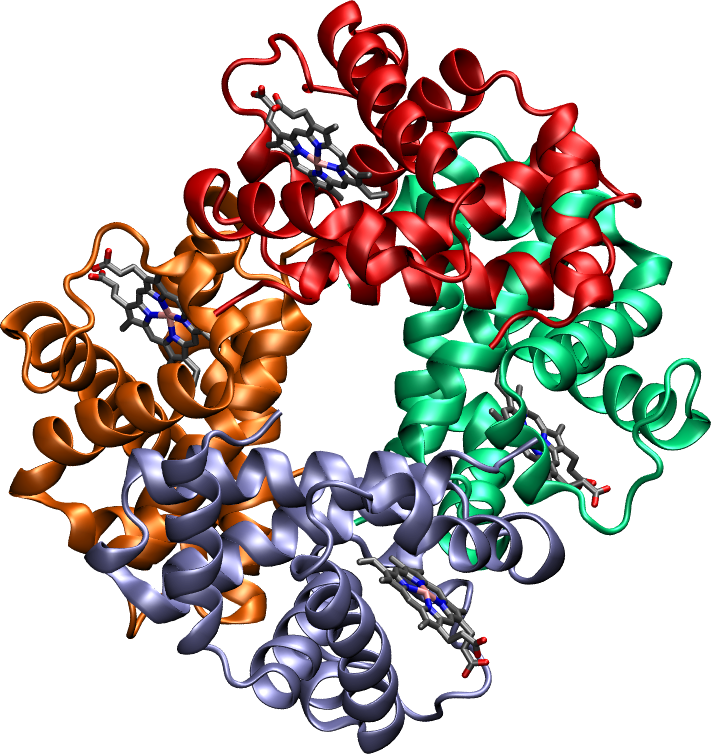

Figure 1:A protein (hemoglobin) represented in two different ways: (a) as a collection of atoms, shown as Van der Walls spheres, and (b) by putting emphasis on the covalent bonds that connect the atoms. The colour coding is: carbons are black, oxygens are reds, nitrogens are blue, phospori are yellow.

Proteins (an example of which is shwon in Figure 1, are macromolecules composed by amino acids linked by peptide bonds. Let’s understand what these two things are.

1Amino acids¶

An amino acid (AA) is a molecule that consists of

an amino group: A functional group containing nitrogen, written as . At neutral pH (pH ) this group is protonated, i.e. it becomes .

a carboxyl group: A functional group consisting of a carbon atom double-bonded to an oxygen atom and bonded to a hydroxyl group, written as . At neutral pH (pH ) this group is negatively charged by donating a proton, becoming . Note that the carbon of this group is often named to distinguish it from the carbons of the side chains.

a side chain (R group): A variable group that differs among amino acids and determines the characteristics and properties of each amino acid. The side chain can be as simple as a hydrogen atom (as in glycine) or more complex like a ring structure (as in tryptophan).

a central carbon atom () that links together the three foregoing chemical groups plus an additional hydrogen atom.

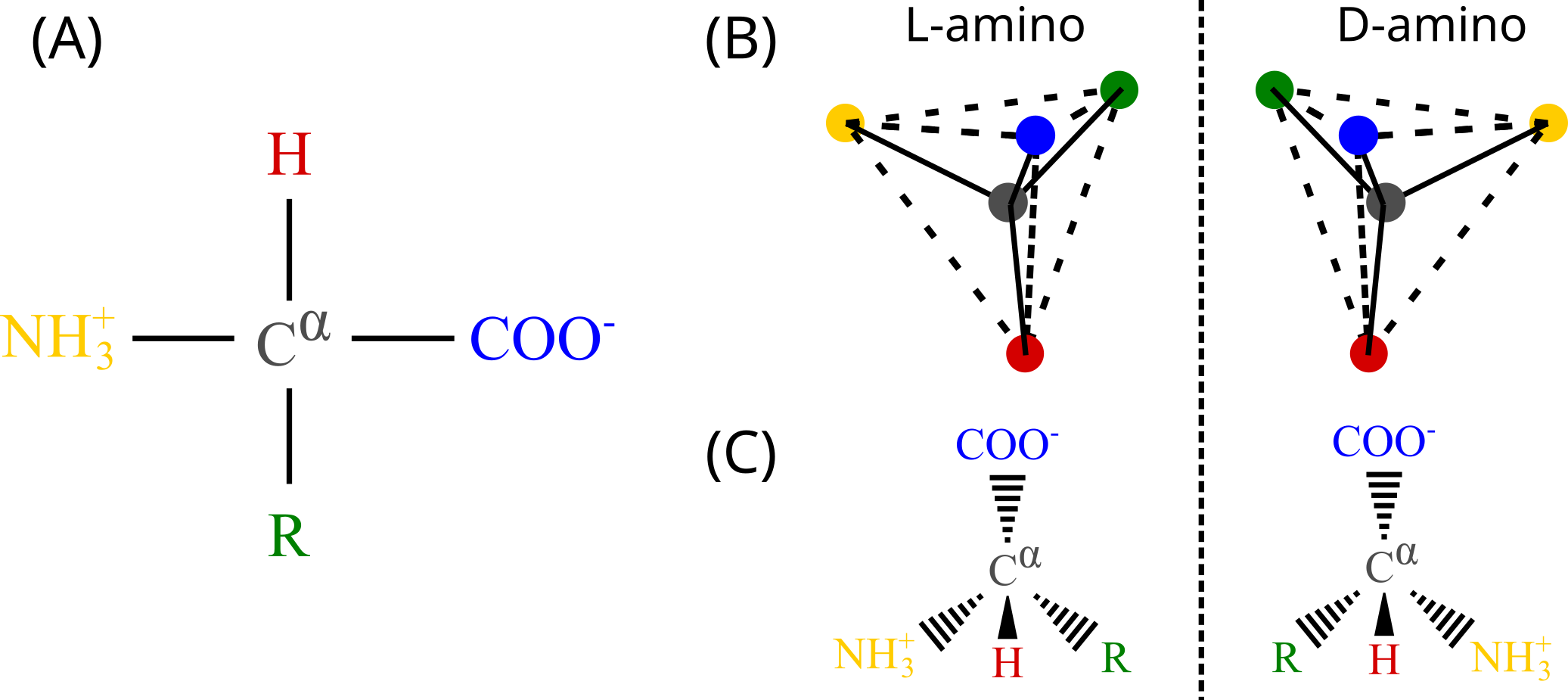

Figure 2:(A) The structure of a generic amino acid with side chain R. (B) A cartoon showing the spatial difference between the left-handed (L) and right-handed (D) amino-acid enantiomers. (C) Another representation showing that looking down the towards the latter, the first letter(s) of the chemical groups read in clockwise order spell out a proper word () for L-amino acids, but a non-existing word () for D-amino acids. In (B) and (C) the chemical groups are coloured as in panel (A).

The four bonds of the are arranged in a tetrahedral fashion, which means that all amino acids but glycine[1] are chiral molecules: each AA can, in principle, exist into two distinct forms that are one the mirror image of the other (i.e. they are enantiomers). Figure 2 shows the chemical structure of amino acids in panel (A), and the two enantiomers in panel (B) with two different representations. For reasons that are not yet understood, most proteins found in nature are made of L-amino acids[2]. By contrast, D-amino acids, which are synthesised by special enzymes, are rare but present in living beings, being involved in some specific biological processes (see e.g. Cava et al. (2010) and references therein).

1.1List of amino acids¶

Given the generic nature of the side chain , there exist countless different amino acid molecules. However, there are 20 standard amino acids that are commonly found in proteins and are encoded by the genetic code. These 20 amino acids are the building blocks of proteins in all known forms of life.

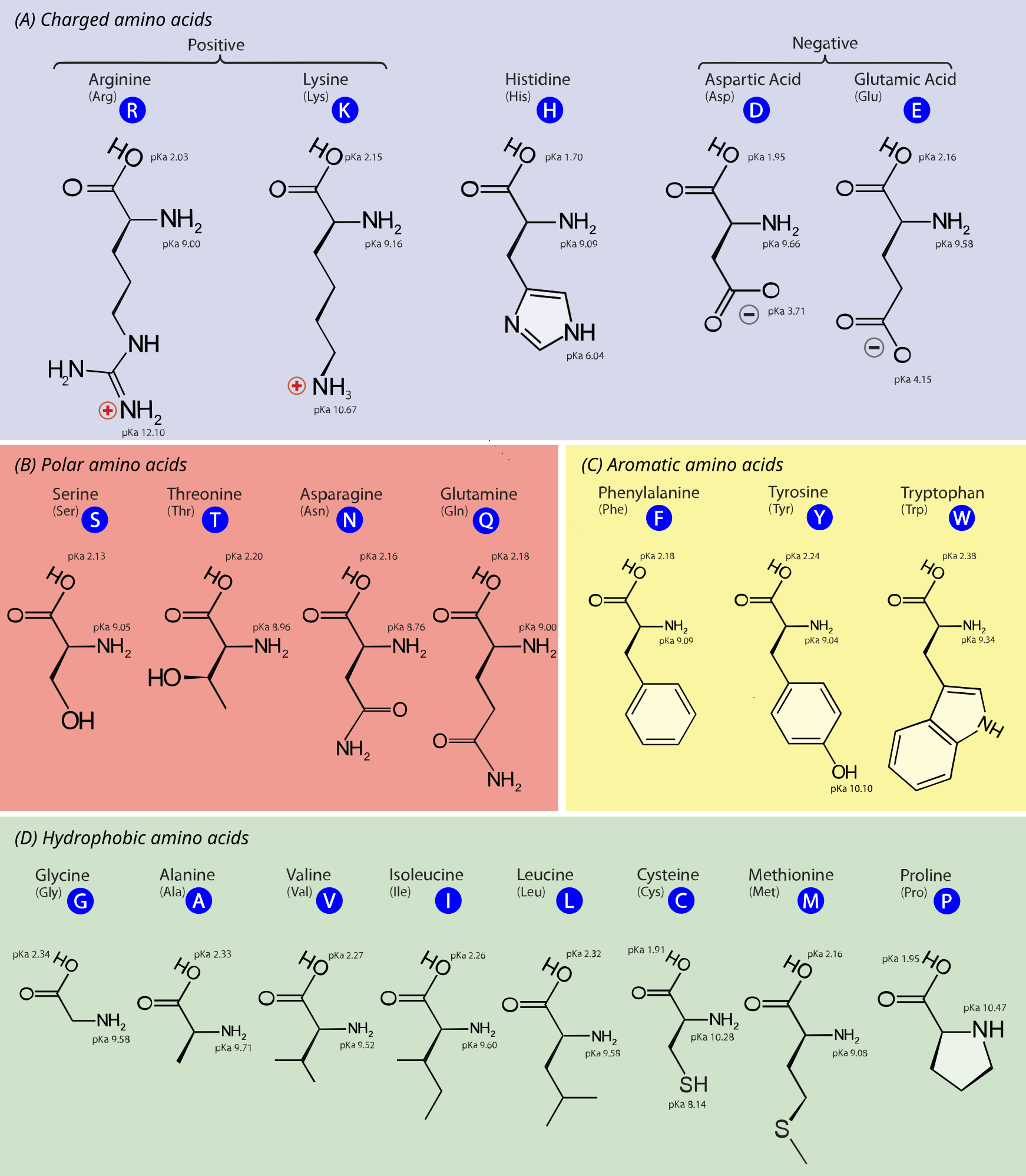

Figure 3:The chemical structure of the 20 standard amino acids. As discussed in the text, the AAs are separated into categories according to the properties of their side chains ( groups). Adapted from here.

Figure 3 shows the chemical structure of the 20 standard amino acids, together with their three- and one-letter abbreviations. In the figure the AAs are grouped in the following classes:

Charged amino acids: AAs with side chains that are charged at physiological pH, making them highly hydrophilic. These are:

Lysine (Lys, K) and Arginine (Arg, R) - positively charged

Aspartic acid (Asp, D) and Glutamic acid (Glu, E) - negatively charged

Histidine (His, H) - being amphoteric, can be positively charged, negatively charged or neutral depending on the pH, playing a role in enzyme active sites.

Polar unchaged armino acids: AAs with side chains that can form hydrogen bonds, making them hydrophilic but not charged at physiological pH. These are:

Serine (Ser, S), Threonine (Thr, T), Asparagine (Asn, N), Glutamine (Gln, Q)

Cysteine (Cys, C) - has been traditionally considered a polar (hydrophilic) AA, but this view has been challenged, which is why here it is listed among the hydrophobic AAs. See for instance Nagano et al. (1999).

Aromatic amino acids: AAs with side chains with aromatic rings, contributing to protein structure and function through stacking interactions. These are:

Phenylalanine (Phe, F), Tryptophan (Trp, W) - the side chains have a strong hydrophobic character

Tyrosine (Tyr, Y) - the presence of the hydroxil group endowes this AA with both hydrophobic and hydrophilic features

Hydrophobic amino acids: AAs with side chains that are hydrophobic and likely to be found in the interior of proteins. These are:

Glycine (Gly, G), Alanine (Ala, A), Valine (Val, V), Isoleucine (Ile, I), Leucine (Leu, L), Methionine (Met, M), Proline (Pro, P)

Cysteine (Cys, C) - has been traditionally considered a polar (hydrophilic) AA, but this view has been challenged, which is why here it is listed among the hydrophobic AAs. See for instance Nagano et al. (1999).

Note that in amino acids, the carbon atoms in the side chains are named systematically based on their position relative to the alpha carbon . The naming convention is to use successive Greek letters (and possibly numerals for branched side chains) to denote each carbon atom, where the beta carbon, , is attached to , follows the beta carbon, and so on and so forth.

Here are some examples:

In alanine the side chain has only one carbon, the beta carbon .

In leucine the side chain has four carbons and branches at the gamma carbon, so that the names are and .

In lysine the side chain has four carbons: , and .

1.2Post-translational modifications¶

Post-translational modifications (PTMs) are chemical changes that occur to amino acids in proteins after they have been synthesized by ribosomes during the translation process. These modifications are essential for the proper functioning, regulation, and localization of proteins within the cell. PTMs can influence a protein’s activity, stability, interactions with other molecules, and overall role in cellular processes. They are critical in the fine-tuning of protein functions and can affect the protein’s behavior in various physiological contexts.

One of the most common types of PTMs is phosphorylation, which involves the addition of a phosphate group () to specific amino acids within the protein, typically serine, threonine, or tyrosine. A phosphate is charged and hydrophilic, so that its addition to side chains alters the interaction with nearby amino acids, making phosphorylation a key regulatory mechanism that can activate or deactivate enzymes, receptors, and other proteins, thereby modulating signaling pathways and cellular responses. This modification is reversible and can be dynamically regulated by kinases (which add phosphate groups) and phosphatases (which remove them), allowing for precise control of protein function.

Another important PTM is glycosylation, where carbohydrate groups are attached to specific amino acid, often asparagine (N-linked glycosylation) or serine/threonine (O-linked glycosylation). Glycosylation plays a critical role in protein folding, stability, and cell-cell communication. It can also affect the protein’s immunogenicity and its recognition by other molecules, influencing processes such as immune responses and cellular adhesion.

Additional types of PTMs include ubiquitination, where ubiquitin proteins are attached to lysine of a target protein, marking it for degradation by the proteasome[3]. Acetylation, the addition of an acetyl group () to lysine, can impact protein stability and gene expression by modifying histones and other nuclear proteins. Methylation, the addition of methyl groups (), typically occurs on lysine and arginine and can regulate gene expression and protein-protein interactions.

Finally, a very common PTM is the hydroxylation of proline, whereby a proline’s pyrrolidine ring gains a hydroxyl () group. It is one of the main components of collagen which, as we will see in a few lessons, is a structural protein that provides strength, support, and elasticity to connective tissues throughout the body.

2The peptide bond¶

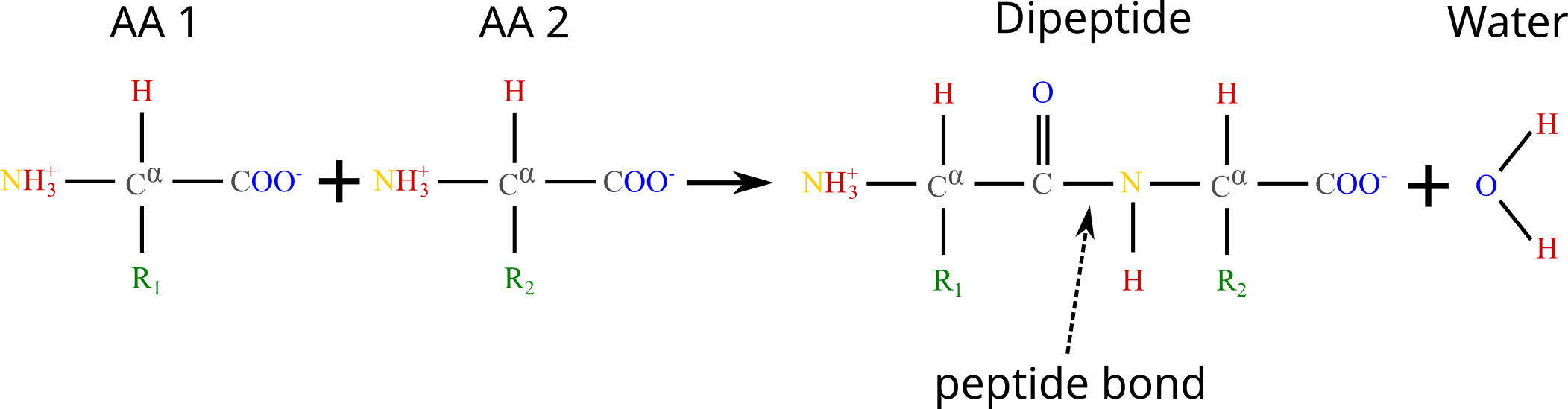

Two amino acids can be linked together through a peptide bond, which is a covalent bond that connects the carboxyl group () of one AA to the amino group () of the other. The reaction through which a peptide bond is formed is called “dehydration synthesis” since the carboxyl group loses a hydroxyl group (), and the amino group loses a hydrogen atom (), which combine to form a water molecule () that is released in solution. Once an AA has been incorporated into the growing chain and the water molecule has been removed, what remains of the molecule is called an amino acid residue, or just residue. Note that under physiological conditions this reaction is not spontaneous, and therefore requires catalysis (usually performed by ribosomes).

Figure 4:The formation of a dipeptide through a dehydration synthesis: two amino acids are joined together, and a water molecule is subsequently released. The peptide bond is indicated by the arrow.

Figure 4 shows the chemical reaction that takes place when two amino acids are joined together, highlighting the peptide bond that links them. The generic term for a chain of amino acids connected by peptide bonds is polypeptide, which is a class of biopolymers that comprises (but is not strictly equivalent to) proteins. While there is some ambiguity in the definition, a polypeptide is considered to be a protein when it takes a specific three-dimensional structure[4] and a well-defined biological function. Note that by this definition a protein is not necessarily formed by a single polypeptide chain. Indeed, there are many proteins, like hemoglobin, that are made of multiple polypeptide units linked by non-covalent bonds (see Section 9 for a more comprehensive discussion on this matter).

The linear sequence of amino acids that are covalently linked together by peptide bonds to form a polypeptide chain is called the primary sequence of a protein. The primary sequence is the most basic level of protein structure and dictates the specific order in which amino acids are arranged, and it determines the protein’s ultimate shape and function through interactions that lead to higher levels of structural organization which we will discuss later on. As a result, any changes or mutations in the primary sequence can significantly impact the protein’s overall structure and function.

2.1Trans and cis conformations¶

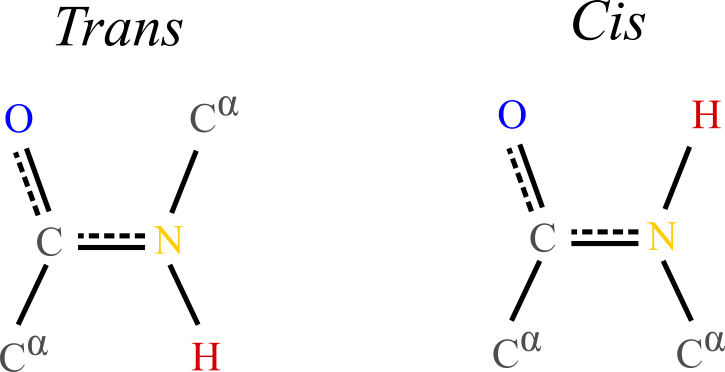

Figure 5:Typical trans and cis conformations of the backbone portion of a single amino acid. In the trans conformation the alpha carbons and their attached side chains are opposite to each other, making this configuration much more stable than the cis conformation, which is rarely observed in proteins.

The planarity of the peptide bond means that amino acids can take two distinct conformations around it:

Trans conformation: the alpha carbon atoms of the adjacent amino acids are positioned on opposite sides of the peptide bond. This arrangement is more stable and commonly observed in proteins because it minimizes steric hindrance between the carbons and side chains of the amino acids.

Cis conformation: the alpha carbon atoms of the adjacent amino acids are positioned on the same side of the peptide bond. This conformation is less stable due to increased steric clashes between the carbons and side chains, making it less common.

The trans conformation is energetically favorable and typically found in the vast majority of peptide bonds in proteins, while the cis conformation can be found in certain regions of proteins, especially involving the amino acid proline, whose unique cyclic structure partially stabilises the cis conformation.

3Molecular vibrations¶

The length of chemical (covalent) bonds is of the order of an angstrom, with , and being almost exactly , being , and and the peptide bond being in between ().

Regarding covalent bond angles, these depend on the nature of the hybridization. We are primarily concerned with sp- and sp-hybridized atoms, which result in planar (approximately ) and tetrahedral (approximately ) structures, respectively. In polypeptides, sp hybridization is observed in the carbon and nitrogen atoms of the peptide bond, while sp hybridization is seen in the alpha carbon, which forms four bonds, and in oxygen and sulfur atoms, which typically form two bonds.

As we will discuss later, vibrations of bond lengths and angles have characteristic frequencies associated to the infrared (IR):

The bond lengths of interest have typical frequencies that go from Hz for to Hz for (corresponding to 1000 cm and 3000 cm, respectively)

Bond angles have typical frequencies of to Hz for , to Hz for , and to Hz for (500 to 1200 cm for the total range).

The values of these typical frequencies can be compared to the thermal energy, , by using Planck’s relation, , which yields

Noting that this value is roughly half of the lowest vibrational or bending frequency reported above, we can conclude that thermal energy does not significantly impact bond stretching and angle bending vibrations[5]. As a result, covalent bond and angle vibrations contribute very little to the conformational flexibility of polypeptides, at least under normal conditions.

By contrast, the typical frequencies of rotations around single bonds are generally much lower than those of bond stretching or bond angle bending vibrations. In fact, some of these frequencies are in the range that is accessible by thermal energy at room temperature, endowing polypeptides with a rotational flexibility that is essential for their conformational dynamics, allowing them to adopt various functional states.

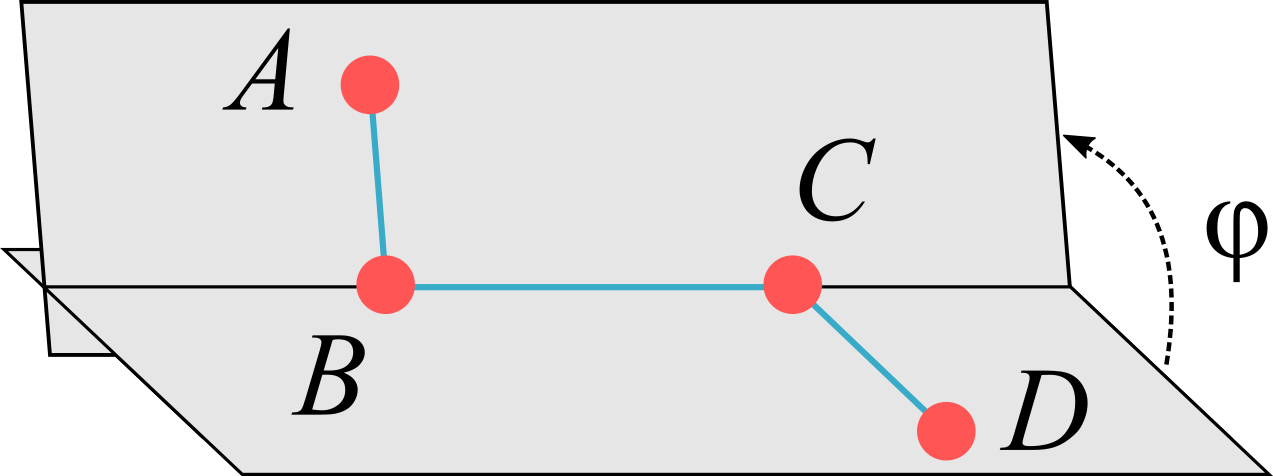

Figure 6:The dihedral angle is defined as the angle formed by the planes determined by the and atoms, which are connected by covalent bonds represented by blue lines. Note that in this picture only one of the two possible choices for the angle, i.e. the dihedral angle , is shown explicitly (see text for details).

The rotation angle around a bond is called torsional or dihedral angle, which, as shown in Figure 6, is the angle formed by two intersecting planes determined by the positions of four atoms. Given the four atoms in figure, , let be the vector connecting two covalently linked atoms and . Given the ambiguity of defining the normal to a plane, the definition of the torsional angle requires a convention. If we choose to define the normal vector to the plane as , the two normal vectors to the plane are

We can now define two torsional angles, , , as the angles between the normal vectors, viz.

The two angles are connected by the relation . Following Schlick (2010), I will call the dihedral angle, and the torsional angle, although the two terms are often used interchangeably.

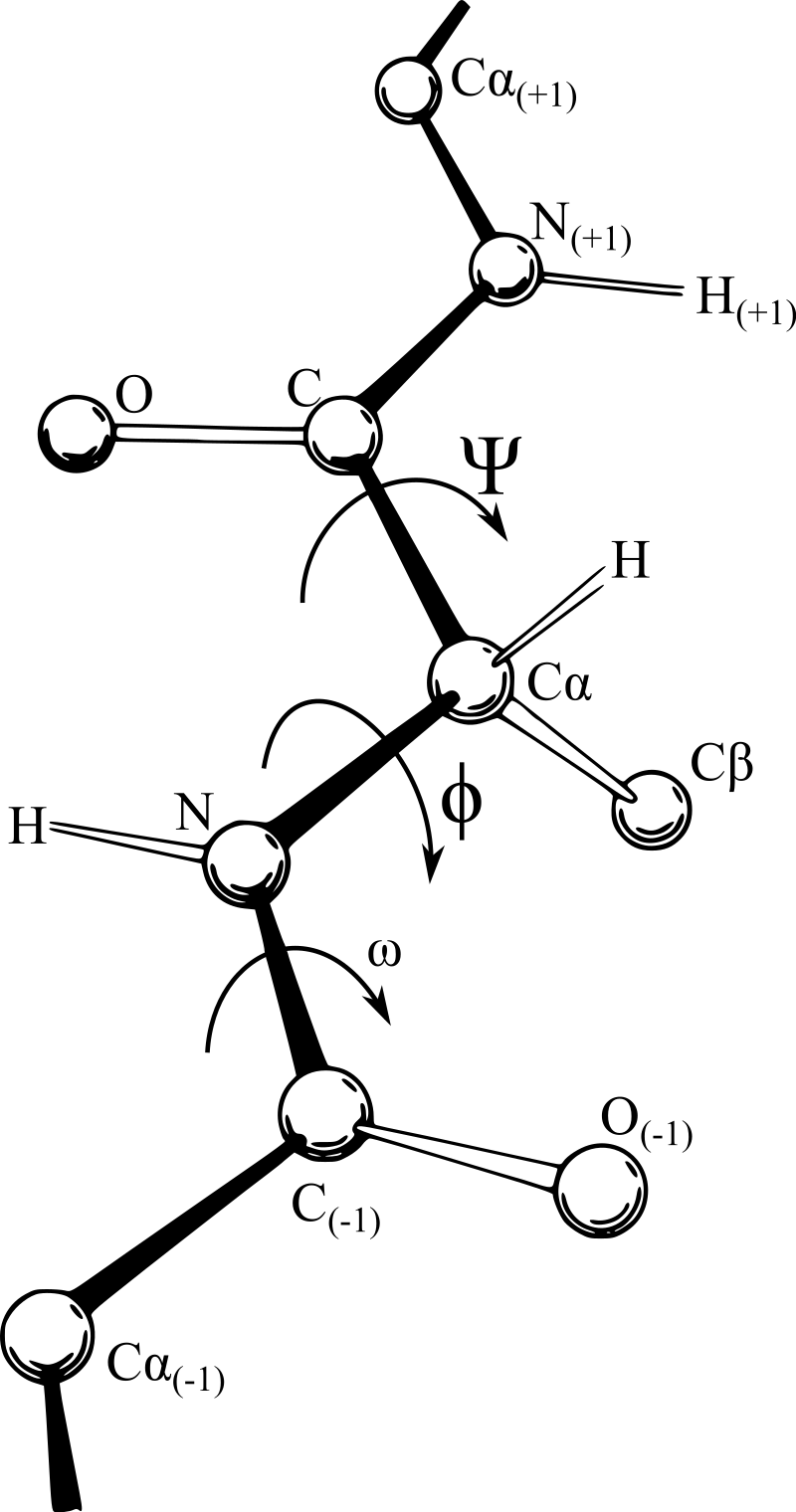

As noted above, the peptide bond, whose associated dihedral angle is called , has a partial double-bond character that restricts rotations around it. The peptide bond is considered to be “planar”, i.e. that the dihedral angle takes values (trans) or (cis), with the latter, as we said, being somewhat less common. Deviations from these values are considered to be rare, but this view has been challenged (see e.g. Berkholz et al. (2011)).

By contrast, rotations around bonds that connect sp- and sp-hybridized atoms are associated to energy barriers that are of the order of and therefore are the main contributors to the flexibility of the macromolecules. In the main chains of peptides the dihedral angles involved in these rotations are those associated to the and bonds, which are called and .

Figure 7:A polypeptide backbone showing the definition of the dihedral angles , and . Credits to Dcrjsr and Adam Rędzikowski via Wikimedia Commons.

A graphical representation of a part of a polypeptide backbone with its associated dihedral angles is shown in Figure 7.

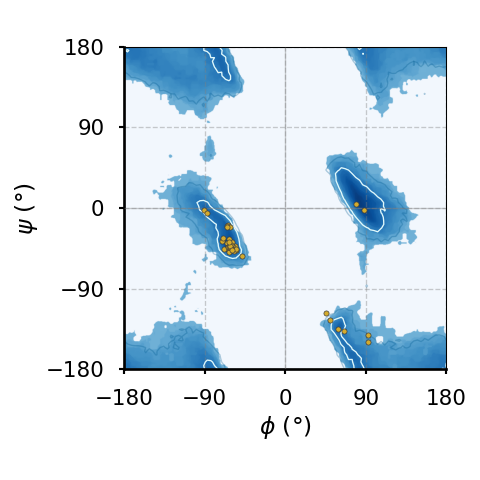

3.1Ramachandran Plots¶

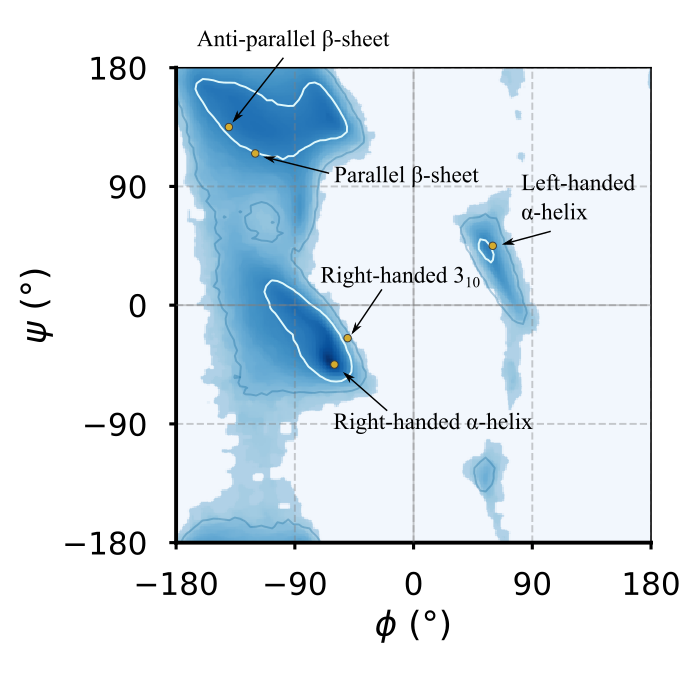

The small energy barriers associated to rotations around and only take into account the atom themselves, not the rest of the molecule to which they are attached. Steric hindrances, resulting from the repulsive interactions between atoms and groups attached to the , and atoms, disfavor or even prohibit certain combinations of values.

A graphical representation of the allowed and disallowed dihedral angles of amino acid residues in protein structures is the Ramachandran plot, introduced for the first time in Ramachandran et al. (1963). By plotting and on the and axes, respectively, the plot reveals regions where the angles are sterically favorable, corresponding to common secondary structures and motifs like -helices and -sheets which will be introduced below. This visualization is crucial for validating protein structures, as it highlights conformational possibilities and identifies potential structural anomalies (i.e. AA conformations that lie in disallowed regions of the plot).

Given a protein structure, it is possible to extract and plot the and values obtained for each residue on the same figure. However, different amino acids display different flexibilities depending on their associated side chains. Therefore, it is common to produce multiple Ramachandran plots, each serving specific purposes and providing insights into various aspects of protein structure and conformation. The most common ones are:

Glycine Ramachandran Plot: glycine residues have more conformational freedom due to the absence of a side chain, and therefore a wider range of allowed and angles compared to the general case, reflecting the famous enhanced flexibility of this AA.

Pre-Proline Ramachandran Plot: residues that precede proline in the primary sequence often exhibit distinct conformational preferences given by the steric influence of proline.

Proline Ramachandran Plot: proline residues have restricted and angles due to the cyclic nature of its side chain, resulting in a limited range of conformations, highlighting the unique structural constraints of this AA.

Ile-Val Ramachandran Plot: the branched carbons of isoleucine (Ile) and valine (Val) give them a distinct shape of disallowed - regions.

General Ramachandran Plot: and angles for all residues that are not part of one of the foregoing categories.

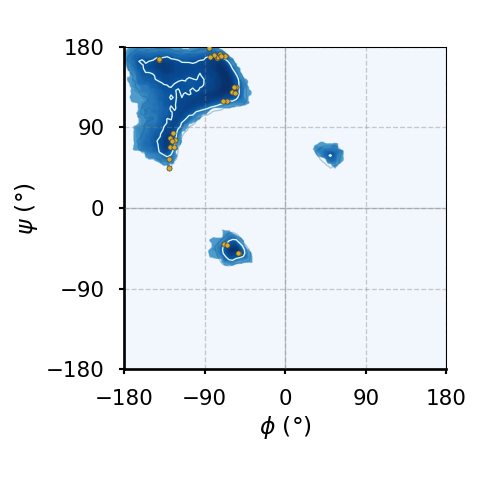

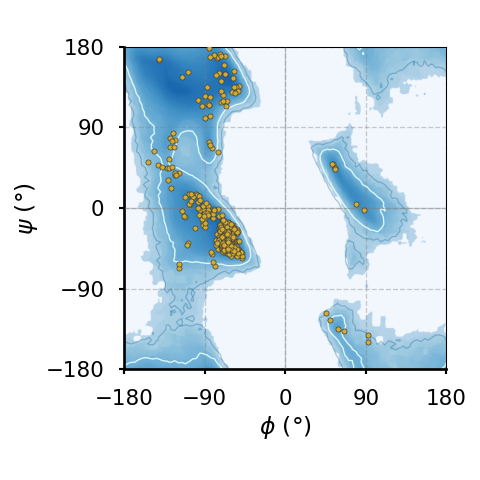

(a)The Ramachandran plot of glycines.

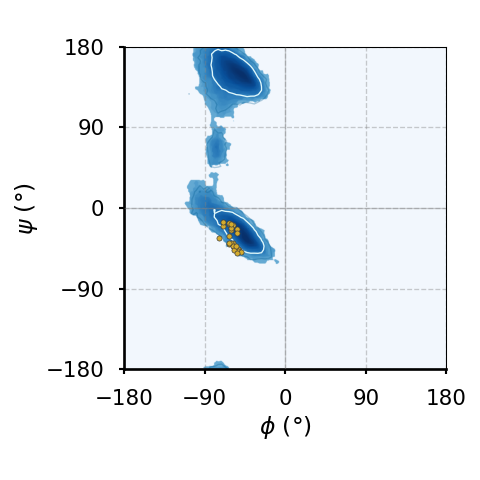

(b)The Ramachandran plot of residues that precede a proline ("pre-proline").

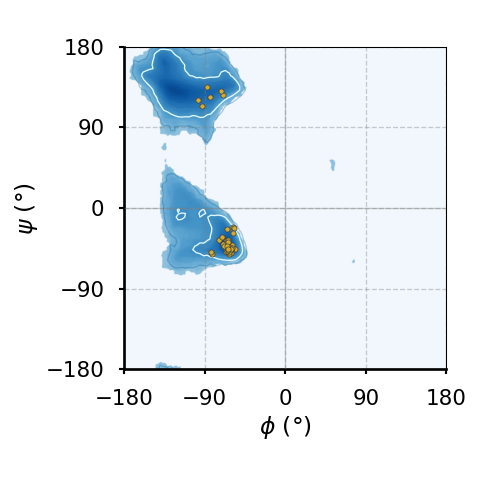

(c)The Ramachandran plot of prolines.

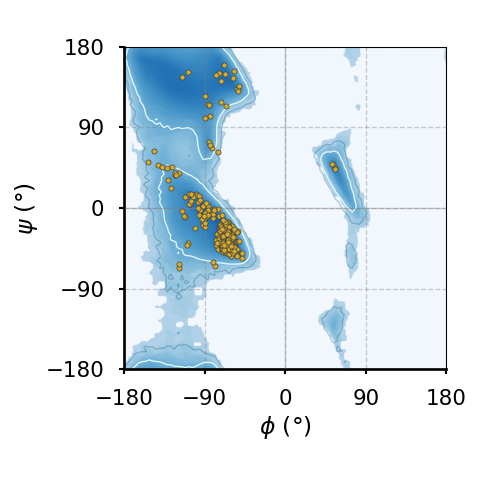

(d)The Ramachandran plot of of leucines and valines.

(e)The Ramachandran plot of all amino acids that are not part of any of the above classes (also known as "general plot").

(f)The Ramachandran plot of all amino acids.

Figure 8:Ramachandran plots of amino acids that compose the human hemoglobin protein 1A3N (points), plotted on background 85th and 75th centiles contour lines, white and blue lines, respectively, generated by analysing the Top8000 PDB data set. I have used a modified version of this software to make the plots.

Figure 8 shows examples of the plot types described above, with the empty (non-coloured) “space” being associated to angle combinations that are sterically forbidden. The points in the panels refer to the combinations of the residues of the human hemoglobin protein, while the background contour plots have been calculated by extracting the values of and from 8000 reference protein structures listed in a database[6].

A comparison between Figure 8a and the other plots shows that glycine has a much greater conformational flexibility than any other AA. By contrast, pre-prolines and prolines (and, to a smaller extent, leucines and valines) are much more constrained than an average AA.

3.2Non-covalent interactions¶

A closer look at the plots also reveals that configurations are forbidden, while are infrequent but not entirely disallowed. What is the difference between these two situations? And, more generally, what causes the shape of the Ramachandran plots?

The “forbidden” regions on this plot correspond to combinations of these angles that result in significant steric clashes and unfavourable interactions, making these conformations highly improbable or energetically unfavorable. These interactions are termed noncovalent, since they arise between pairs of atoms that are not involved in a bond. I will briefly sketch the most important noncovalent interactions in this context. Of course, as shown in Figure 8, the absolute and relative importances of these terms depend not only on the nature of the amino acid, but also on its local environment.

3.2.1Van der Waals interactions¶

The most prominent reason for the forbidden regions is steric hindrance, where atoms are positioned too closely together, leading to repulsive forces. This happens when the dihedral angles place the backbone or side chain atoms in close proximity, causing overlaps or severe crowding, making some conformations energetically unfavorable.

The atom-atom repulsion is a general phenomenon occurring when electron clouds belonging to atoms with fully-occupied orbitals overlap. The repulsion is caused by the Pauli exclusion principle, which prevents two electrons from occupying the same quantum state, and it is a steeply increasing function of the decreasing interaction distance. It is common to model the functional dependence of the repulsive interaction energy on , the interatomic distance, with the (heuristic) form , which is not based on first-principles calculations but is computationally cheap and good enough for most purposes (Leach (2001), Schlick (2010)).

When the atom-atom interdistance is sufficiently larger, quantum mechanical effects lead to attractive forces (the most important being the famous dispersion or London force) that arise from temporary dipoles induced in atoms or molecules as electrons move around. In general, the total attractive contribution is the sum of three contributions having the same functional dependence on distance, (see e.g. Israelachvili (2011)).

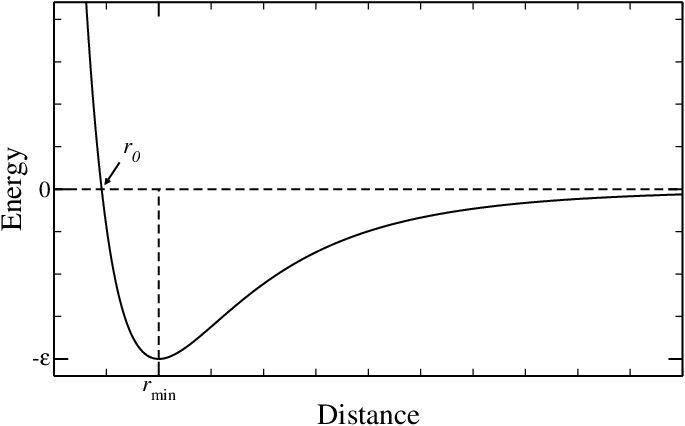

Figure 9:The Lennard-Jones potential, often used to model van der Waals interactions.

The total interaction, which is the sum of the two terms, is termed van der Walls interaction and is often modelled with the famous Lennard-Jones (LJ) potential, viz.

where is the depth of the minimum arising from the competition between attraction and repulsion, and is its position. A plot of the LJ potential is presented in Figure 9. The figure highlights an additional length, , which is the distance at which the energy becomes positive, and therefore can be seen as an estimate for the minimum distance below which two atoms “clash”[7]. Therefore, the value that takes for each pair of noncovalent interaction can be useful to estimate the stability of a given conformation.

Table 1:Typical values for the parameters of the van der Walls interaction between same-type atoms (listed in the first column), as reported in Finkelstein & Ptitsyn (2002).

| Atom | (kcal / mol) | at 298 K | () | () |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.12 | 0.20 | 2.4 | 2.0 | |

| 0.12 | 0.20 | 3.4 | 3.0 | |

| 0.23 | 0.39 | 3.0 | 2.7 | |

| 0.20 | 0.34 | 3.1 | 2.7 |

Typical values for , and for the main self interactions, i.e. interactions between atoms of the same type, are listed in Table 1. Note that the interaction strengths are always smaller than at ambient temperature. In the case of mixed interactions between atoms of type and , there exist several combining rules to estimate the values of the van der Waals parameters (see Leach (2001) for a discussion). The most common are the Lorentz-Berthelot rules, which amount to taking the arithmetic mean for the radii and the geometric mean for the energy strengths:

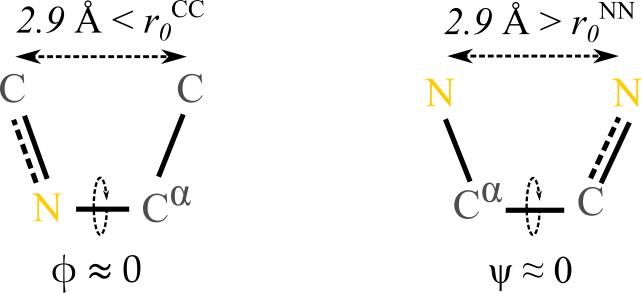

Figure 10:Cis conformation over (left) and over (right). The numbers above the dashed lines are the average distances between (left) and (right) atoms.

We are now equipped to rationalise our observation that values of are forbidden, while conformations with are infrequent but not impossible. The difference between the typical conformations having these dihedral values can be appreciated by looking at Figure 10: in both cases the two 1-4 atoms connected to the atoms involved in the bond that defines the dihedral lie in the same half-plane and are roughly at the same distance (). However, in the case the two atoms are both carbons, which have a “minimum allowed distance” of , making this conformation essentially forbidden. By contrast, in the case both atoms are nitrogens, so that the minimum allowed distance is , which is smaller than the actual distance: according to the effect of this 1-4 interaction, this conformation is allowed.

Of course, even if we look at the contributions due to van der Waals forces only, there are other atom-atom interactions that forbid specific conformations. These interactions involve mostly the oxygen, the alpha carbon and the hydrogen of the backbone, but also the side chains. However, in the latter case the main contributor is the beta carbon, which is why the only AA lacking it, glycine, has a distinctively different Ramachandran plot.

3.2.2Hydrogen bonds¶

Certain combinations of and angles can prevent the formation of hydrogen bonds, which are particular bonds that can link amino acids between them and with water molecules (or other solutes): if the backbone dihedral angles do not permit optimal hydrogen bonding, the conformation is unlikely to be stable or favorable. But what is a hydrogen bond?

A hydrogen bond (HB) is a type of weak chemical bond that occurs when a hydrogen atom, which is covalently bonded to an electronegative atom (like oxygen, nitrogen, or fluorine), experiences an attraction to another electronegative atom in a different molecule or a different part of the same molecule, and can be understood in terms of electrostatic interactions. Indeed, atoms like nitrogen, oxygen, and fluorine are highly electronegative, meaning they have a strong tendency to attract electrons. In a molecule, when hydrogen is covalently bonded to an electronegative atom, the shared electron is drawn closer to it, creating a partial negative charge on it and a partial positive charge on the hydrogen atom which generates an uneven distribution of electron density. If the hydrogen atom comes close enough to another electronegative atom having a partial negative charge, the electrostatic interaction between the opposite partial charges will give raise to an effective attraction. This effect can create reversible bonds between different molecules, or between different parts of the same molecule.

Notable examples in this context are mainly those in which there are and atoms involved: , , , etc., where is shorthand for a hydrogen bond. In all these cases, the atom covalently bound to the hydrogen (or sometimes the whole group) is called the donor, while the other one (or the molecule it is part of) is the acceptor. As a rule of thumb, the number of HBs that an electronegative atom can accept is equal to its number of lone pairs[8], which is one for nitrogen and two for oxygen.

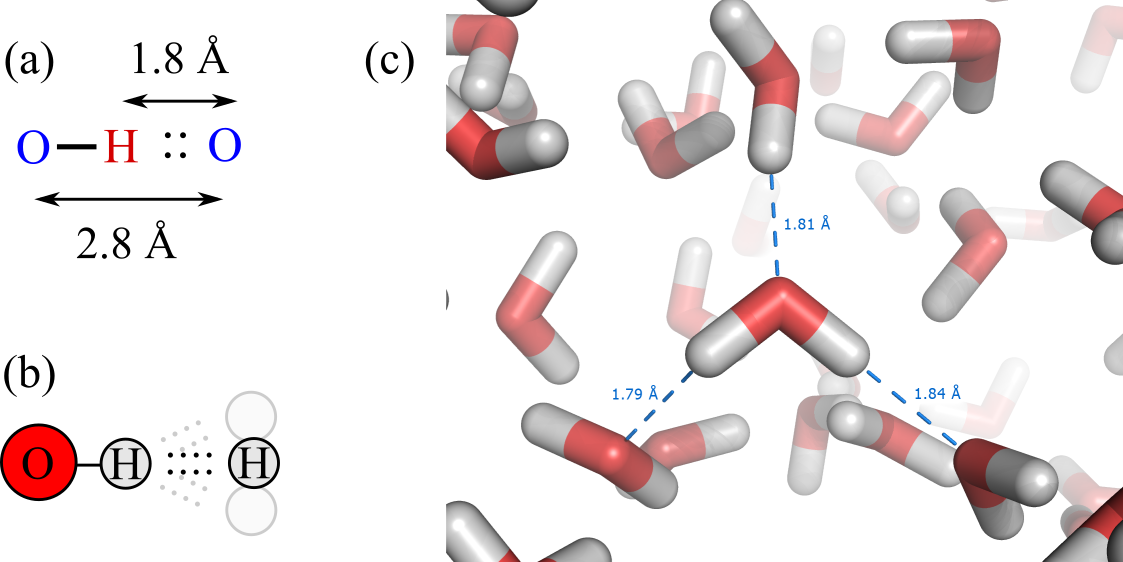

We now look at the geometry of a hydrogen bond. In a HB, the distance between the acceptor and the hydrogen atom varies slightly depending on the specific molecules and environmental conditions, but typically ranges from 1.8 to . As a result, the distance between the acceptor and the atom covalently bonded to the hydrogen is close to , the optimal van der Waals distance for interactions involving and/or . A fundamental property of hydrogen bonds is that, unlike in van der Waals interactions, HBs are highly directional: their strength depends on the relative orientations of the chemical groups involved. Specifically, the optimal hydrogen bond occurs when the donor atom, hydrogen atom, and acceptor atom are aligned linearly, with an angle close to . Deviation from this linear alignment results in weaker hydrogen bonds, or even bond breakage if it exceeds .

Figure 11:(a) Typical distances in a hydrogen bond. (b) Optimal hydrogen bonds are linear, but small deviations are possible. (c) Hydrogen bonds in a liquid water molecular dynamics simulation, with some acceptor-hydrogen distances highlighted (credits to Splette and Wikimedia).

Figure 11 shows a schematic view of the main properties of hydrogen bonds, together with a simulation snapshot of liquid water where some hydrogen bonds are explicitly highlighted.

The importance of HBs on the association of molecules can be appreciated by looking at the following table, which shows the melting and boiling temperatures at ambient pressure, and , of 3 molecules of similar weight:

| Molecule | # of HBs | Molecular weight | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Methane, | 0 | 16 g/mol | ||

| Ammonia, | 1 | 17 g/mol | ||

| Water, | 2 | 18 g/mol |

Since carbon is very weakly electronegative, it does not form any hydrogen bond. As a result, association in methane, as embodied by the values of and , happens at very low temperature, where the attraction is provided by van der Waals interactions only. However, as electronegativity (and the number of lone pairs) increases from to and then , HBs become more and more relevant, substantially increasing the melting and boiling temperatures.

Following Finkelstein & Ptitsyn (2002), the strength of hydrogen bonds can be estimated by comparing the (latent) heat of vaporization[9] of molecules that are composed by the same atoms, e.g. dimethyl ether , 5 kcal / mol, and ethanol, , 10 kcal/mol. Since the latter has an group that the former lacks, there is an additional contribution of the latent heat due to one HB per molecule which amounts to kcal/mol. A similar estimate can be made by using the heat of vaporization of ice (we will see why in a moment), which is kcal/mol. Of this value, kcal/mol are due to van der Waals interactions, as estimated by looking at the evaporation of analogous, but non-HB-forming, molecules (e.g. or ). The rest is provided by the two hydrogen bonds that each water molecule can form, yielding again an energy gain of kcal/mol per HB. Recalling that, at room temperature, kcal / mol, we can estimate that one HB provides , suggesting that the formation of hydrogen bonds is highly favoured under ambient conditions. The order of magnitude of this value is intermediate between the van der Waals interaction strength, which is a fraction of (see the table reported in the previous section), and the strength of covalent bonds, which amounts to hundreds of kJ / mol ().

In water, hydrogen bonds are the main driving force for condensation and ice formation. Since each oxygen can accept two bonds, and each hydrogen can mediate one donor-acceptor interaction, each water molecule can be involved in four bonds that are arranged on a (nearly perfect) tetrahedron. This geometry can be rationalised as follows. In general, electron pairs (both bonding and lone pairs) around a central atom will arrange themselves to minimize repulsion, but the repulsion between lone pairs is greater than the repulsion between bonding pairs. Consequently, the two lone pairs will occupy positions that are as far apart as possible, pushing the bonding pairs closer together. As a result, the four pairs of electrons (two lone pairs and two bonding pairs) around the oxygen atom in water adopt a tetrahedral arrangement to minimize repulsion, with the bond angle between the hydrogen atoms in a water molecule being , slightly less than the ideal tetrahedral angle of due to the greater repulsion exerted by the lone pairs.

Since the natural tetrahedral geometry of water molecules leads to the maximum number of HBs, it should not come as a surprise that regular ice has a diamond cubic cell, where each molecule is connected to four others through (almost) linear hydrogen bonds. When ice melts into liquid water, it releases kcal/mol of heat. In turn, when water turns into vapour at , kcal/mol of boiling heat is released. If we assume that no hydrogen bonds are present in water vapour, we could use these values to estimate that a fraction of breaks when ice melts. However, this is not the case. In fact, it is perhaps surprising that liquid water at ambient conditions has roughly the same number of HBs of ice, i.e. . What happens then when ice melts into liquid water? The hydrogen bonds become looser, and their length and, more importantly, angular fluctuations increase. Of course, these fluctuations have an energetic cost, which is counterbalanced by the entropy provided by the many possible ways of realising disordered networks made of molecules connected by “flexible” hydrogen bonds.

We now go back to proteins, with the working hypothesis that, under ambient conditions, all hydrogen bonds are formed[10]. If we look at the peptide backbone, we see that it contains nitrogen and oxygen, which are polar groups and can be involved in hydrogen bonds. In addition, as discussed before, many side chains are polar, or even charged under physiological conditions. As a result, a polypeptide has many chemical groups that can be involved in hydrogen bonds. What partners do these chemical groups bond to: other polar groups or water molecules?

To answer this question let us consider two chemical groups on the same polypeptide, an acceptor and a donor , that can form a hydrogen bond. Assuming that all hydrogen bonds are formed, there are two possible states: is bonded to , or they are both bonded to water molecules. The equilibrium between these two states can be described by

When and form a HB, the two water molecules are freed to form hydrogen bonds with other water molecules. Since the number of hydrogen bonds on the left-hand side matches that on the right-hand side, the energy remains essentially unchanged. However, entropic contributions must also be considered:

When a hydrogen bond forms between and , the polypeptide’s flexible backbone is typically forced to adopt a more constrained and specific conformation to facilitate this interaction, leading to a loss of conformational freedom and therefore a loss of entropy.

When the intramolecular hydrogen bond forms, the water molecules previously bonded to the polar groups are released into the bulk solvent. These water molecules, previously constrained in position and orientation (low-entropy state), now return to a more disordered state, increasing the system’s entropy

Interestingly, it turns out that, on average, the entropic contributions of these two effects not only have opposite signs but are also comparable in magnitude (see Finkelstein & Ptitsyn (2002) for a more thorough discussion), so that the conformation the backbone adopts is “marginally” stable and depends on the local environment rather than on intrinsic factors.

3.2.3Electrostatic interactions¶

According to classical electrostatic, the interaction energy between two charges and at distance in a homogeneous medium is

where , is the relative dielectric permittivity of the medium and is the absolute permittivity of vacuum. Common values of are for water, for a folded protein and 1 for vacuum (or air). However, we are not dealing with homogenous media, as the distances we consider are very much comparable with inter-molecular separations. In all-atom simulations, solvent and solute atoms and molecules are handled explicitly and therefore there is no “medium” and Eq. (8) is applied with . By contrast, when one is interested in coarse-grained models, where the solvent’s effect is described implicitly, or in theoretical considerations, when the description should be as simple as possible, one has to address the question of how to describe the effect of macromolecular charged groups and their interactions.

Let’s start by considering what happens inside a protein. If we consider two positive charges separated by a distance of , their interaction energy is kcal/mol () in water, while a whopping kcal/mol () in a non-polarisable medium such as plastics or dry proteins (). Such a large repulsion would be enough to destroy a protein, which is usually stabilised by a “reserve” free energy of kcal/mol (Finkelstein & Ptitsyn (2002)). This tells us that charged side chains will not be found close to each other in a protein core. However, we can go further and consider the electrostatic self-energy of a single atom of charge and radius [11]:

Setting and yield the same values we obtained for interacting pairs (i.e. kcal/mol in water, kcal/mol in the protein), meaning that the cost of having a single charged group inside a protein core exceeds the stability of the protein itself. As a consequence, ionisable side chains are nearly always uncharged when embedded in a core, since the free-energy cost of donating or accepting a (to or from water) is much smaller than the energetic contribution due to the electrostatic self-energy of a charge.

Now we can consider what happens outside of the protein. Following Finkelstein & Ptitsyn (2002) we can leverage basic[12] electrostatics in the presence of dielectric materials to find that even close to the protein surface the dielectric constant is much larger than that inside the core (). Thus, the charge-charge interaction strength is always severely reduced compared to the vacuum.

Everything said above rests on the assumption that the medium can be regarded as continous and homogeneous. However, when dealing with atomic distances (), the granularity of the solvent cannot, in principle, be neglected. For instance, if two charges are apart, no atoms or molecules can get in between them and affect the resulting electrostatic interaction. However, it turns out that the water molecules that are attracted by the pair of charges and come from the sides are enough to screen the electrostatic interactions almost as if the solvent were homogeneous and had the “macroscopic” dielectric permittivity .

This result should not be surprising if we think about common table salt, : the binding energy between the and ions, if we again take , is -1.5 kcal/mol and -120 kcal/mol in bulk water () and vacuum (), respectively. Even if the assumption of a perfectly continuous and homogeneous solvent were to break down at short distances, so that the effective dielectric constant were reduced to, say, , the interaction energy would still be -6.0 kcal/mol. This is on the order of the strength of a single hydrogen bond between two water molecules.

If that were the case, we would expect to dissolve only very sparingly: the maximum possible concentration of dissolved salt (i.e. the saturated solution, where no more ions can be accommodated without precipitating back out as solid crystal) would be comparable to the concentration of water molecules in saturated water vapor, which is mol / l (or 10-4 M). In other words, only a very small amount of salt should remain stably dissolved. This observation confirms that the effective dielectric constant of liquid water must remain very high, and therefore close to the bulk value of 80, even when .

3.3Rotamers¶

Almost all amino acids can adopt different orientations of side chains around single bonds. Exceptions are

glycine, which has no rotational freedom in terms of side chain orientation,

alanine, whose side chain is a methyl group, , which is small and symmetrical, offering no significant variation in rotameric states,

proline, whose side chain forms a ring by bonding back to the backbone nitrogen, severely restricting the rotation around its side chain.

The distinct conformations of an amino acid at fixed values of are called rotamers and arise due to the rotation around the bonds connecting the side chains to the main backbone of the polypeptide chain. The dihedral angles connected to the rotamers are referred to as angles, which describe the rotations around the bonds within the side chains of amino acids. Each rotatable bond in a side chain is associated with a specific angle, labeled sequentially from the backbone outward. For instance, is the dihedral angle around the bond between the alpha carbon and the beta carbon, is the dihedral angle around the bond between the beta carbon and the gamma carbon, and so on for longer side chains.

Each amino acid side chain can adopt multiple rotameric states, influenced by steric interactions, hydrogen bonding, and other intramolecular forces. The different rotamers contribute to the overall flexibility and diversity of protein structures, allowing proteins to achieve their functional conformations and interact effectively with other molecules.

4Primary structure¶

The order in which amino acids are linked together by peptide bonds is known as the primary structure of a protein. The convention to list the sequence of a protein is to use the one-letter or three-letter codes for amino acids in the sequence, which has a well-defined directionality. The sequence starts at the end of the amino acid chain that has a free amine group (), which is called N-terminus and, by convention, marks the beginning of a protein. The other end has a free carboxyl group () and is known as the C-terminus, which is considered the end of the protein.

An example

The sequence of bovine (cow) rhodopsin expressed with the one-letter code is

MNGTEGPNFYVPFSNKTGVVRSPFEAPQYYLAEPWQFSMLAAYMFLLIMLGFPINFLTLYVTVQHKKLRTPLNYILLNLAVADLFMVFGGFTTTLYTSLHGYFVFGPTGCNLEGFFATLGGEIALWSLVVLAIERYVVVCKPMSNFRFGENHAIMGVAFTWVMALACAAPPLVGWSRYIPEGMQCSCGIDYYTPHEETNNESFVIYMFVVHFIIPLIVIFFCYGQLVFTVKEAAAQQQESATTQKAEKEVTRMVIIMVIAFLICWLPYAGVAFYIFTHQGSDFGPIFMTIPAFFAKTSAVYNPVIYIMMNKQFRNCMVTTLCCGKNPLGDDEASTTVSKTETSQVAPA

5Visualising molecules¶

When dealing with molecular models, it is very important to be able to visualise the 3D structure of the system. Indeed, visualization tools make it possible to explore the three-dimensional conformation of molecules, helping to identify key structural features (e.g. active sites, binding pockets, regions of flexibility, etc.). When performing simulations, the are many uses for visualisations. Here I will list the main ones:

It is very important to familiarise with the system under investigation: always look at what you simulate!

A big part of setting up complicated simulations is to prepare the initial configuration. This is often a multi-step process, and being able to visually follow this process can speed-up the troubleshooting of possible issues.

Sometimes (often...) simulations provide “wrong” results, either because something went awry during the simulation itself, or because some parameters were incorrectly set. You should always make sure that the final (or equilibrium) configurations of your simulations make sense and match the results you obtain, and visualising them help in this direction.

A big part of doing science is to be able to efficiently and clearly explain your results to an audience. Good figures are fundamental to convey the important messages of your work, and sometimes a visualisation of a 3D structure (or part of a 3D structure) can very efficiently make a point across.

The next two sections will briefly introduce how information about a molecular system can be stored on a computer, and how to visualise a molecular structure.

5.1File formats¶

Figure 12:The proliferation of standards. Credits to xkcd.

For historical (but not only, as shown in Figure 12) reasons, there exist multiple file formats for representing molecular structures, simulation data, and related information. While each main simulation software has its own, there are also some (usually software-agnostic) standard formats that are widely used to share information about molecular structures. In structural and computational biology, the standard is the Protein Data Bank (PDB) file format, originally developed in the 1970s to archive experimental data from X-ray crystallography, NMR spectroscopy, and cryo-electron microscopy. Each PDB file contains a detailed description of the atomic coordinates, connectivity, and sometimes additional information like secondary structure annotations, heteroatoms, and crystallographic data.

The full format specification can be found at this link. Here I will provide a short description based on this one, which should be enough for most use cases. A PDB file is a human-readable text file where each line of information in the file is called a record, and the records are arranged in a specific order to describe a structure. The first part of a PDB file usually contains some metadata, with the most common record types being:

HEADER: a general description of the contents of the file, including the name of the macromolecule, classification, deposition date, and PDB ID.

TITLE: a more detailed description of the structure, often including the protein’s function, any ligands or cofactors, and relevant experimental conditions.

COMPND: the macromolecular components of the structure (e.g. the names of individual protein chains, nucleic acids, ligands, etc.).

SOURCE: the source of each macromolecule (e.g. the organism, tissue, or cell line from which the structure was derived).

KEYWDS: keywords that describe the structure, such as enzyme classification, protein family, or biological process.

EXPDTA: information about the experimental method used to determine the structure (e.g. X-ray crystallography, NMR spectroscopy, cryo-electron microscopy, etc.).

AUTHOR: the names of the researchers who contributed to the structure determination.

REVDAT: the revision history of the PDB file, including the dates of modifications and a brief description of the changes made.

JRNL: reference(s) to the publication(s) associated with the structure determination.

REMARK: more general remarks or comments related to the structure (e.g. experimental details, data processing, etc.).

SEQRES: the primary sequences of the macromolecules stored in the file, with the amino acid or nucleotide residues given by their one-letter codes.

The actual structure and connectivity is stored in records that are usually of the following types:

ATOM: atomic coordinate record containing the coordinates, in , for atoms in standard residues (amino acids and nucleic acids).

HETATM: same as ATOM, but for atoms in nonstandard residues. Nonstandard residues include ions, solvent (such as water molecules), and other molecules such as co-factors. The only functional difference from ATOM records is that HETATM residues are by default not connected to other residues.

TER: indicates the end of a chain of residues.

HELIX: indicates the location and type (right-handed , etc.) of helices, which are secondary structures that will be introduced soon. One record per helix.

SHEET: indicates the location, sense (anti-parallel, etc.) and registration with respect to the previous strand in the sheet (if any) of each -strand, which is another type of secondary structure (see below). One record per strand.

SSBOND: defines disulfide bonds, which are particular bonds linking cysteine residues that will be introduced later.

Each record has a specific format that was designed when punched cards where still common. Therefore, records are made of fields that have a fixed width, and never go beyond 80 columns. Here I report the format of the ATOM, HETATM, and TER records:

| Record Type | Columns | Data | Justification | Data Type |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ATOM | 1-4 | “ATOM” | character | |

| 7-11 | Atom serial number | right | integer | |

| 13-16 | Atom name | left | character | |

| 17 | Alternate location indicator | character | ||

| 18-20 | Residue name | right | character | |

| 22 | Chain identifier | character | ||

| 23-26 | Residue sequence number | right | integer | |

| 27 | Code for insertions of residues | character | ||

| 31-38 | coordinate | right | real (8.3) | |

| 39-46 | coordinate | right | real (8.3) | |

| 47-54 | coordinate | right | real (8.3) | |

| 55-60 | Occupancy | right | real (6.2) | |

| 61-66 | Temperature factor | right | real (6.2) | |

| 73-76 | Segment identifier | left | character | |

| 77-78 | Element symbol | right | character | |

| 79-80 | Charge | character | ||

| HETATM | 1-6 | “HETATM” | character | |

| 7-80 | same as ATOM records | |||

| TER | 1-3 | “TER” | character | |

| 7-11 | Serial number | right | integer | |

| 18-20 | Residue name | right | character | |

| 22 | Chain identifier | character | ||

| 23-26 | Residue sequence number | right | integer | |

| 27 | Code for insertions of residues | character |

The following excerpt, taken from the PDB file of human hemoglobin, shows how a PDB file looks like:

HEADER OXYGEN TRANSPORT 22-JAN-98 1A3N

TITLE DEOXY HUMAN HEMOGLOBIN

...

AUTHOR J.TAME,B.VALLONE

...

REMARK 2

REMARK 2 RESOLUTION. 1.80 ANGSTROMS.

REMARK 3

REMARK 3 REFINEMENT.

REMARK 3 PROGRAM : REFMAC

REMARK 3 AUTHORS : MURSHUDOV,SKUBAK,LEBEDEV,PANNU,STEINER,

REMARK 3 : NICHOLLS,WINN,LONG,VAGIN

...

HELIX 1 1 PRO A 4 SER A 35 1 32

HELIX 2 2 PRO A 37 TYR A 42 5 6

HELIX 3 3 ALA A 53 ALA A 71 1 19

HELIX 4 4 MET A 76 ALA A 79 1 4

HELIX 5 5 SER A 81 HIS A 89 1 9

...

ATOM 219 CB ARG A 31 -2.135 3.057 22.133 1.00 6.25 C

ATOM 220 CG ARG A 31 -3.684 3.130 22.122 1.00 7.07 C

ATOM 221 CD ARG A 31 -4.155 4.091 21.001 1.00 7.50 C

ATOM 222 NE ARG A 31 -5.608 4.102 20.966 1.00 8.30 N

...

TER 4374 HIS D 146

HETATM 4375 CHA HEM A 142 8.456 12.968 30.943 1.00 12.71 C

HETATM 4376 CHB HEM A 142 6.923 14.956 26.818 1.00 15.63 C

HETATM 4377 CHC HEM A 142 8.220 10.950 24.353 1.00 9.88 C

HETATM 4378 CHD HEM A 142 9.359 8.784 28.599 1.00 7.91 C

...

END5.2Software tools¶

There are many software tools that make it possible to visualise and interact with molecular models. Here is a (very non-comprehensive) list:

VMD is open source. It supports many formats, handles large systems efficiently, and has numerous plugins available and powerful scripting capabilities. However, its interface is rather ugly (especially compared to the other visualisation tools), and many functionalities can be complex for beginners.

PyMol is open source. It can be used to (more or less) easily producing high-quality, publication-ready images and animations, it has an extensive user community and good documentation and powerful scripting capabilities with Python. However, it can be get slow with very large molecular systems, and it can be complex for beginners to master all features and functionalities.

Chimera[14] is not open source, although its source code is available. It is the most intuitive and easy to use software presented here, especially for beginners, and it has excellent visual quality for creating publication-quality images, supports a wide range of file formats and integrates well with other bioinformatics tools. It has somewhat less powerful scripting capabilities compared to VMD and PyMOL, and ChimeraX has some features behind a paywall.

I urge you to install and try at least one of these programs. Use this file, which I used to generate Figure 13, or this real protein file to test the software. In Chimera and PyMol you can directly open the file, while with VMD you’ll have to create a new molecule (File New molecule... Browse Load) and choose a sensible representation (Graphics Representations... and then pick e.g. “NewCartoon” from the “Drawing method” menu).

6Secondary structure¶

The secondary structure of proteins refers to the local, repetitive folding patterns of the polypeptide chain. These structures are stabilized primarily by hydrogen bonds between the backbone atoms in the polypeptide chain, specifically between the carbonyl oxygen () of one amino acid and the amide hydrogen () of another.

The most common secondary structures found in proteins are helices (and -helices in particular) and -sheets.

6.1Helices¶

A helix of length is a repetitive structure whereby the group of the -th AA in thee chain is hydrogen-bonded to the group of a -th residue, for consecutive values of . In protein systems, a helix is identified by a name , where:

is the number of residues per helical turn;

is the number of atoms in the ring closed by a hydrogen bond. For instance, the rings formed in a regular helix are 7: (where the latter belongs to the -th AA).

is the handedness of the helix: if we look down a helix (i.e. if AAs with higher index come towards us) and the -th AA is staggered in the counterclockwise direction with respect to the -th the helix is right-handed (R), otherwise is left-handed (L).

The helices that appear in proteins are , (also known as -helix) and (also known as helix). Note that they are all right-handed[15]. The -helix is uncommon since its open structure disfavours some stabilising van der Waals interactions, and it is rarely (if ever) present in canonical (i.e. regular) form[16]. Therefore, we will not consider it any further.

Given the periodicity of a helix, there are optimal values of and that maximize efficient atomic packing and precisely align the peptide bonds, thereby stabilizing the helical structure. These values, together with other properties of the two most common helices, are reported in the table below:

| Helix | HB pattern | Residues per turn | Pitch () | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3 | 6.0 | ||||

| -helix () | 3.6 | 5.4 |

Since both these helices are usually right handed, I will drop the sub- and superscript.

In helices, the side chains (R groups) of the amino acids are oriented outward from the helical axis: If you imagine looking down the helical axis, the side chains would appear as spokes radiating out from the central helical core. Due to the helical twist, the side chains are staggered along the length of the helix, so that they are not directly above or below each other, and they are tilted back towards the N-terminus, giving them a slightly downward orientation relative to the helical axis.

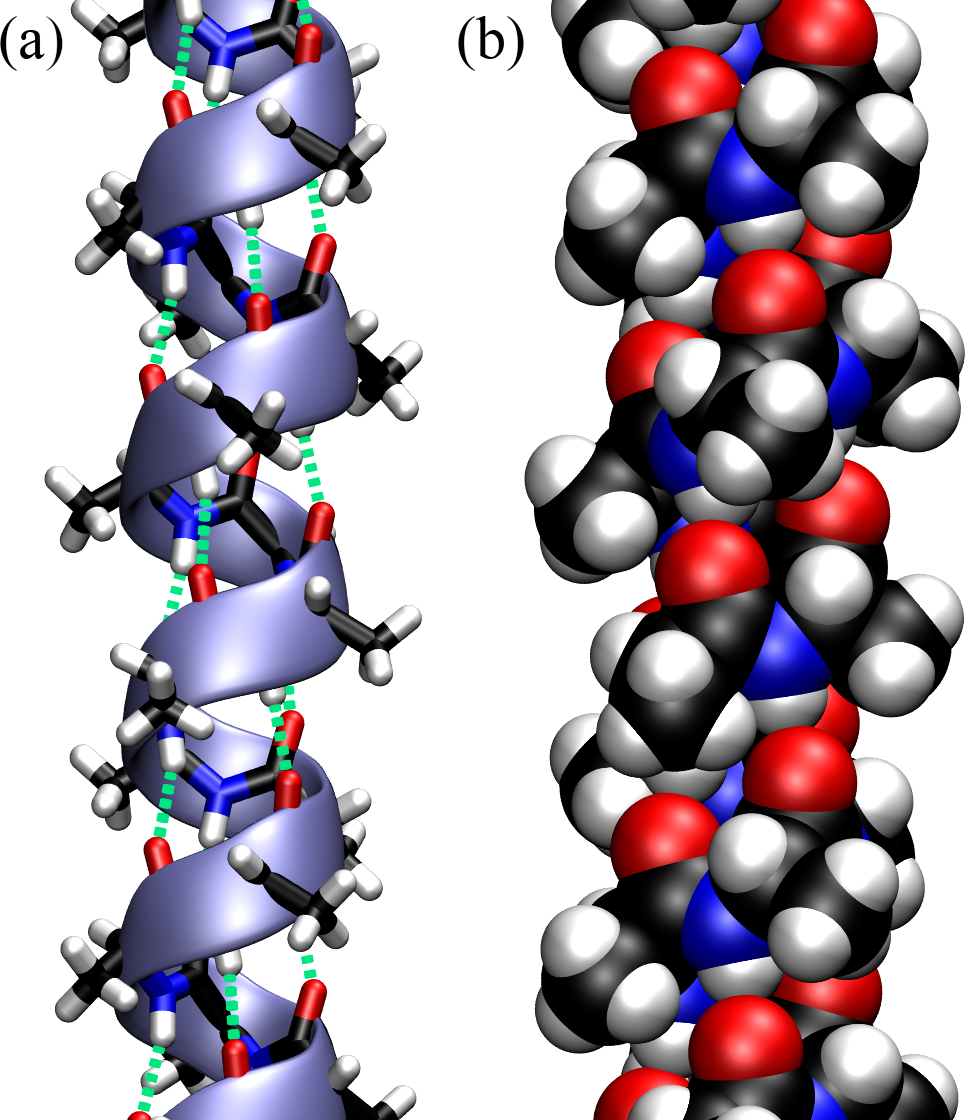

Figure 13:An -helix made by a polypeptide made of consecutive Ala. (a) Licorice representation, where the atoms and the bonds have the same diameter, superimposed with a ribbon that follows the backbone and shows the helical turns. The hydrogen bonds that stabilise the structure are shown with green dashed lines. (b) The same helix with the atoms represented as van der Waals spheres.

Figure Figure 13 shows an optimal -helix made with a Python library that makes it possible to build polypeptides specifying the sequence and the geometry (in terms of and ). The polypeptide is composed of consecutive Alanine residues with and , and it is shown with different representations:

The licorice representation, also known as “ball-and-stick”, where atoms are small spheres and bonds are cylinders, and everything has the same diameter, is very useful to look at molecular connections.

Ribbon-like and/or wireframe representations are very useful to understand the organisation in terms of secondary structures.

Drawing atoms as van der Waals spheres, also known as space-filling representation, makes it possible to appreciate the efficient packing of folded structures, but it is otherwise rather limited in its utility since it leaves only the protein surface visibile.

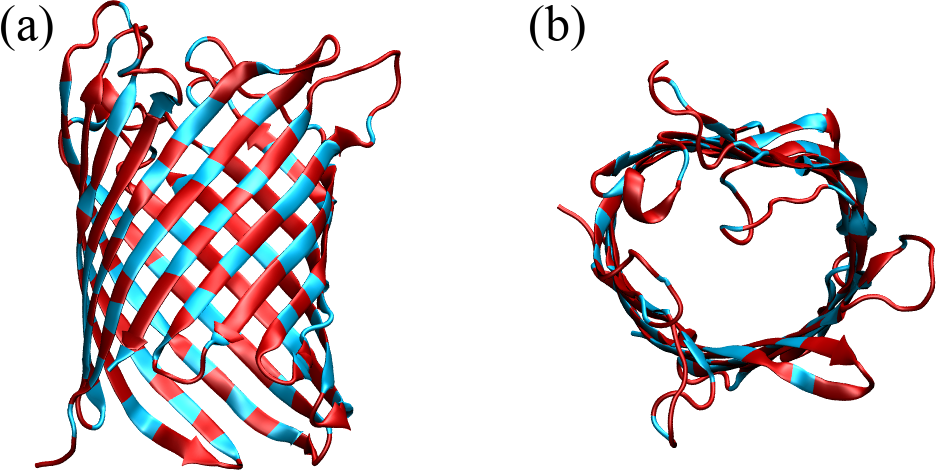

6.2-structures¶

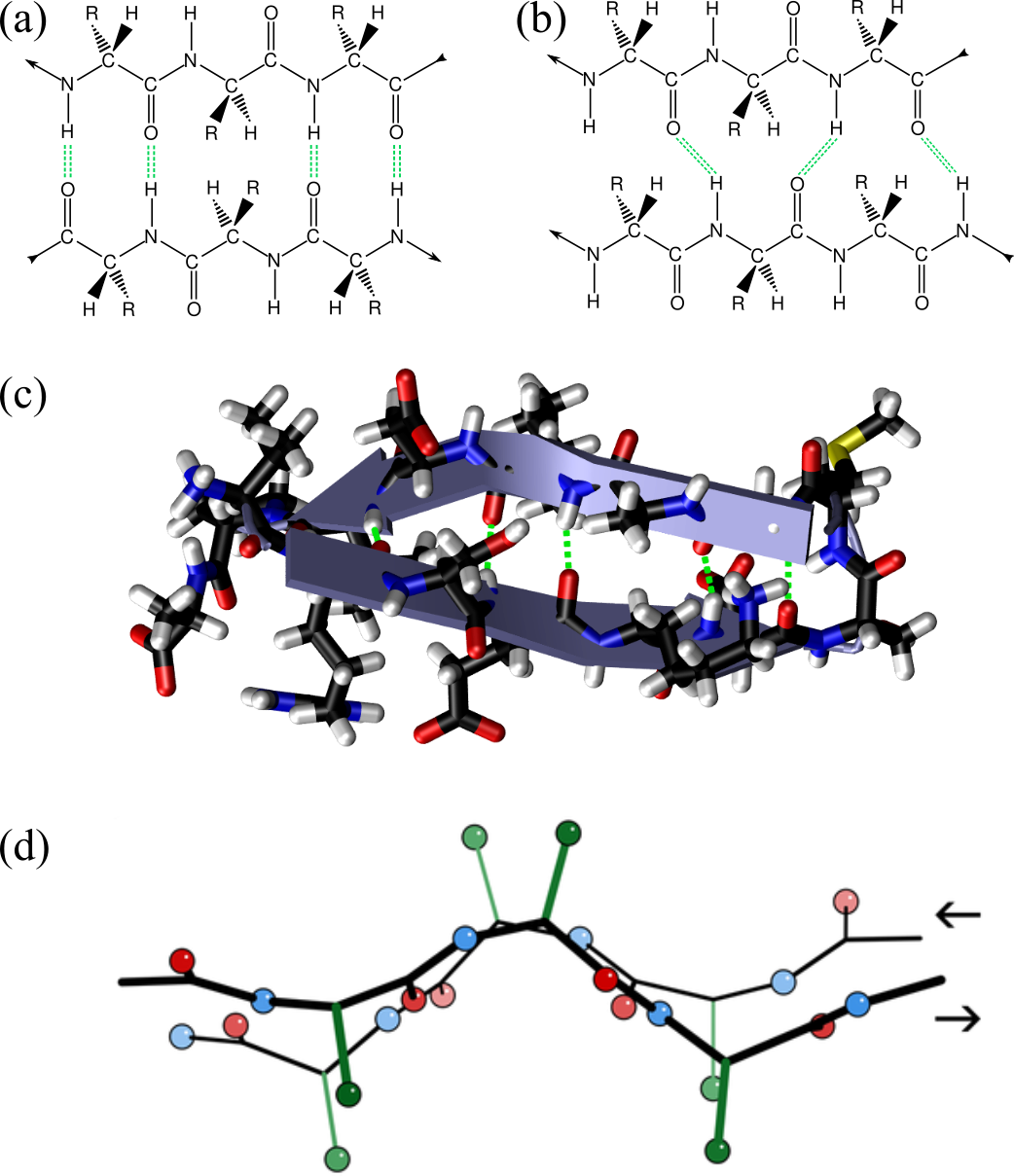

-structures (or -sheets) comprise the other class of common secondary structures. -structures are formed by -strands, which are stretches of polypeptide chain, typically 5-10 amino acids long, in an extended conformation. Unlike the helical structure presented above, -strands are not stable per se, but they are stabilised by hydrogen bonds formed with other strands. In fact, two or more -strands can connect laterally by backbone hydrogen bonds to form a sheet-like array termed -sheet. Since the backbone has a directionality (), the lateral connection joins strands that either run in the same direction or not:

In an antiparallel -sheet, which is the most common motif in proteins, adjacent strands have alternating N-terminus and C-terminus orientations.

In a parallel -sheet, the N-termini of adjacent strands are oriented in the same direction.

Figure 14:Two segments of a chain form a -sheet by connecting through hydrogen bonds (green dashed lines). The arrows at the beginning and at the end of the segments show the chain directionality. The two segments run anti-parallel and parallel to each other in (a) and (b), respectively (adapted from here). In (c) the X-ray structure of the first 18 residues of Fumarase C where the ribbon representation (“Cartoon” in VMD) is superimposed to the atomic structure and clearly shows the presence of a -hairpin: two anti-parallel -strands connected by a short turn. Panel (d) shows two anti-parallel -strands fragments taken from the crystal structure of the Micrococcus Lysodeikticus catalase, where the hydrogens are omitted for clarity, and only the first carbons of the side-chain carbon are shown (in green). Credits to Dcrjsr via Wikimedia commons.

The hydrogen bonds form between the carbonyl oxygen of one amino acid in a strand and the amide hydrogen of an amino acid in the adjacent strand. As shown in Figure 14, in antiparallel sheets, these hydrogen bonds are more linear and stronger, contributing to greater stability compared to the less linear hydrogen bonds in parallel sheets. Parallel -sheets containing 4 or fewer strands are not common, which may be due to the lower stability provided by the sub-optimal geometry of their hydrogen bonds. Figure 14(c) shows a 3D conformation of a short protein fragment that adopts a rather common -sheet conformation called “-hairpin”, where two anti-parallel -strands are connected by a short turn.

The last panel of Figure 14 shows two other important properties of -sheet:

In a fully extended -strand, the side chains of amino acids point straight up and straight down in an alternating fashion. When -strands align to form a sheet, their atoms are positioned next to each other, with the side chains from each strand pointing in the same general direction. As a result, if a side chain points straight up, the bond to the carbonyl carbon must angle slightly downward due to the tetrahedral bond angle, endowing the strands with a “pleated” appearance[17].

-strands usually have a right-handed twist arising from a combination of the chiral nature of L-amino acids, geometric constraints of peptide bond angles, and the need to optimize hydrogen bonding and minimize steric hindrance (see e.g. Chothia (1973)). The hydrogen bonds that stabilize a sheet do not eliminate the twist of individual strands but rather accommodate it, leading to a twisted sheet. Parallel strands tend to be more twisted.

The preferred dihedral angles of parallel and anti-parallel -sheets are reported in the table below:

| Type | ||

|---|---|---|

| Parallel, | ||

| Anti-parallel, |

6.3Irregular secondary structures¶

Irregular secondary structures in proteins are regions that do not conform to the regular patterns of -helices or -sheets. These structures include loops, turns, and coils, and they play important roles in the overall shape and function of proteins. First of all, these structures can serve as linkers or hinge regions that facilitate the movement of domains within a protein, and make it possible to adopt multiple conformations necessary for function.

Moreover, they are often exposed to the solvent, where they can form hydrogen bonds that compensate for the lack of regular secondary structure, mitigating the high energy cost associated with broken hydrogen bonds. This, in turn, makes them accessible for interactions with other molecules, such as substrates, inhibitors, and other proteins.

Here is a breakdown of the most common irregular secondary structures:

Loops are flexible regions that connect -helices and -sheets. They do not have a regular, repeating structure, and often occur on the surface of proteins and are involved in interactions with other molecules or proteins. They can also contribute to the active sites of enzymes.

Turns are short sequences of amino acids that cause a sharp change in direction of the polypeptide chain. They typically involve 4-5 amino acids and are critical for the compact folding of proteins. They often occur at the ends of -strands, facilitating the formation of antiparallel -sheets through the formation of -hairpins (see Figure 14(c) for an example). Some very short turns (4 AAs) are known as -turns and are stabilised by a hydrogen bond.

Coils are non-repetitive, flexible regions without a defined secondary structure. They are sometimes referred to as random coils, though they are not truly random. Coils provide flexibility and enable conformational changes in proteins. They often link regular secondary structures and can be involved in binding and recognition processes.

7Hydrophobic interactions¶

As we will see in later lectures, the main driver for protein compaction (folding) is hydrophobicity. In general, a molecule’s solubility in water is a crucial property that can be determined experimentally. By comparing the concentrations of various substances dissolved in water, we can ascertain which molecule is more soluble. This comparison reveals water’s affinity for different solutes, essentially indicating which substances are more favorably integrated into the aqueous environment. Comparing the outcome of such experiments on, say, sugar and oil would make it clear that the former is much more hydrophilic (“water-lover”) than the other, which has a strong hydrophobic (“afraid of water”) character. Systematic experiments show that uncharged molecules or chemical groups that cannot form hydrogen bonds are hydrophobic and, when put in water, tend to shy away from the water molecules, clustering together.

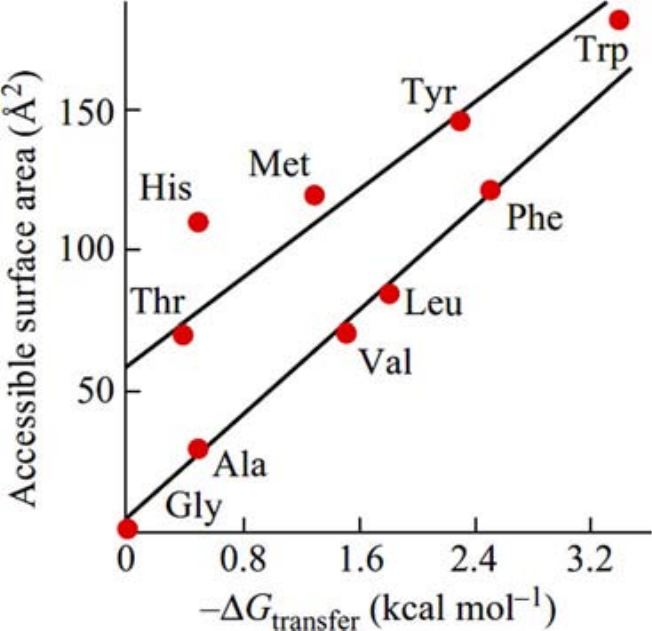

In order to explore this effect, we consider hydrocarbons as model systems, since many non-polar amino acids feature hydrocarbon side chains (see the classification of amino acids sketched above), and refer to the free-energy difference of transferring a substance from a nonpolar or slightly polar solvent to water, . The nonpolar solvent containing the solute molecules, which in the simplest case can be the bulk liquid of the substance of interest, is put in contact with water through a semipermeable membrane that allows the transfer of the solute only. When the equilibrium is reached, the chemical potential of the solute is the same in the bulk and in water, viz.

where , the and subscripts refer to the water and bulk systems, respectively, is the concentration of the substance of interest in the system , is a constant to make the argument of the logarithms dimensionless, and is its excess (with respect to the ideal gas) chemical potential. The difference between the excess chemical potentials of the two systems can be evaluated from the (experimentally measurable) values of and through

This quantity is the free-energy cost of moving one molecule from the bulk to the water, also known as the solvation free energy, [18]. In turns out that this cost is approximately proportional to the molecule’s accessible nonpolar surface area , as described by the relationship kcal/mol, where is the surface (or interfacial) free energy (see Figure 15). This relationship implies that larger nonpolar surface areas result in greater free-energy costs for solvation. Interestingly, the free-energy cost increases with temperature, highlighting that the entropic contribution, , plays a major role in the process.

Figure 15:The solvation free energy as a function of the accessible surface area of amino acid side chains. Note that for both quantities the value associated to glycine (which has no side chain) has been substracted prior to plotting. The side chains of Ala, Val, Leu, Phe consist of hydrocarbons only; those of Thr and Tyr additionally have one OH-group each, Met an SH-group, Trp an NH-group, and His an N-atom and an NH-group. Therefore, their accessible non-polar area is smaller than their total accessible surface. Taken from Finkelstein & Ptitsyn (2016).

But what causes entropy to decrease when a hydrophobic molecule is inserted into an aqueous solvent? The effect arises from the high cost of breaking hydrogen bonds in liquid water. Indeed, when a nonpolar solute is introduced, water molecules reorient around the solute to maintain as many hydrogen bonds as possible in order to avoid breaking existing hydrogen bonds, which would be energetically very expensive. This reorientation, while preserving hydrogen bonds, restricts the movement of water molecules and effectively “freezes” their orientations, leading to a decrease in entropy. It is these ice-like water molecules that causes the anomalously high heat capacity of hydrocarbons such as cyclohexane, , which can increase by up to an order of magnitude in an aqueous solvent (“iceberg effect”).

The hydrophobic effect, which is the observation that non-polar substances are immiscible with water because of entropic effects, is very important in determining the stability of proteins. In fact, proteins that live in aqueous environments[19] have a core composed by non-polar AAs whose formation is, by and large, driven by hydrophobic forces. The origin of these forces can be understood by considering two hydrophobic objects with accessible surface area and , respectively. The cost of solvating the two objects when they are far from each other is , where is the extent of the hydrophobic surface. However, if the two objects approach each other, the nonpolar surface area exposed to water decreases, leading to fewer water molecules with ‘frozen’ orientations, which in turn reduces the entropic cost associated with solvating the objects. As a result, the solvation free energy decreases, . Therefore, a state where hydrophobic surfaces are close enough that no water molecule can slip in is thermodynamically favoured with respect to a state where the same surfaces are far from each other.

7.1Structured water¶

Around hydrophilic regions of the protein, water molecules form hydration shells through hydrogen bonds and electrostatic interactions while, as we have just seen, near hydrophobic regions, water molecules cannot form hydrogen bonds with the protein surface, but they reorient to maximize hydrogen bonding among themselves while minimizing disruption. In both cases there is the appearance of structured water, which is an organized arrangement of water molecules in the immediate vicinity of the protein surface.

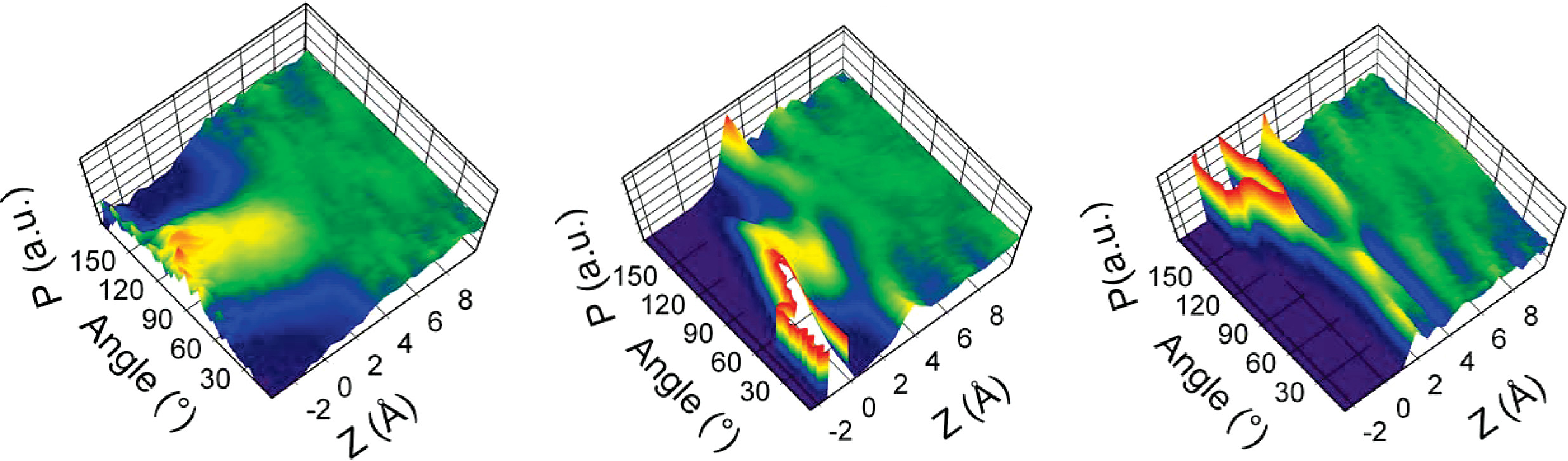

Figure 16:Bidimensional distributions of water molecules as function of their dipole orientation and distance from the surface. Left: liquid-vapor interface; middle: hydrophilic talc (001) surface; right: hydrophobic mica (001) surface. The probability is normalised by the atomic density at the given distance. Red (blue) means higher (lower) probability.. Adapted from Wang et al. (2009).

The hydration layers around the protein have a restricted mobility and orientation that reduce their ability to respond to an applied electric field, in turn affecting the dielectric constant, which takes values that, depending on the distance from and type and geometry of the protein’s surface, can be much lower than in the bulk (where ). The reduced dielectric environment enhances electrostatic interactions between charged groups, possibly influencing protein folding, stability, and interactions with other molecules, such as substrates, inhibitors, or other proteins.

Moreover, structured water around proteins exhibits slower dynamics compared to bulk water, which significantly impacts protein behavior and function. For instance, it can also influence the rates of enzymatic reactions by modulating the flexibility and movement of active site residues.

8Tertiary structure¶

Figure 17:The Ramachandran general plot of the Top8000 PDB data set, with contour lines highlighting the 80th and 95th centile in blue and white, respectively. The yellow circles are the optimal dihedral angles of the regular secondary structures introduced in the previous section, where those of the left-handed -helix are the same as the -helix, taken with the opposite signs.

The tertiary structure of proteins refers to the overall three-dimensional shape of a single polypeptide chain, resulting from the folding and interactions of its secondary structural elements. Let’s start by considering what is the geometry of the single residues that are part of well-folded proteins[20], which, as discussed before, at first order we can assume to be fully described by the and dihedrals.

Figure 17 shows the general[21] Ramachandran plot of 8000 well-characterised proteins, as well as the positions of the optimal secondary structure elements (perfect helices and -sheets). It is evident that the majority of residues have dihedrals that are compatible with regular secondary structures. However, the probability distribution is not perfectly peaked at the optimal values (particularly for -sheets), and it also exhibits considerable width. One obvious reason for this is that while there is a single “optimal” conformation for a given secondary structure, it is entropically favorable to adopt conformations that are close to this optimal state without incurring significant energetic penalties.

Additionally, and more interestingly, secondary structures interact with each other and pack together to fold into the native state of the protein. To achieve this, residues must accommodate various constraints and interactions imposed by neighboring structures. These interactions include steric hindrances, electrostatic forces, and hydrogen bonding, which can cause deviations from the optimal dihedral angles. As a result, the conformations observed in Ramachandran plots reflect a balance between maintaining the overall stability of the secondary structures and allowing the flexibility required for proper folding and function, leading to broader, less sharply peaked distributions.

The regions in the Ramachandran plot that are far from those associated to regular secondary structures are usually populated by residues that are in an irregular (or even disordered) structure such as a coil or a loop.

Most proteins are generally either densely packed structures or composed of densely packed domains. The primary driving force behind the formation of these packed domains is the hydrophobic effect, which tends to compact the hydrophobic side chains into a central core that excludes water molecules. In terms of purely hydrophobic interactions, the resulting “molten globule” would be liquid, resembling an oil droplet. However the presence of additional interactions - such as van der Waals interactions, hydrogen bonds, ionic bonds, and disulfide bridges (which we will discuss shortly) - further solidifies the protein, endowing it with the stability and shape-retaining properties essential for its biological function (Finkelstein & Ptitsyn (2002)).

Now I will (very!) briefly discuss how secondary structures pack and layer to form the native structures of proteins. Following Finkelstein & Ptitsyn (2002), we classify folded proteins into three macrocategories: fibrous, membrane and globular proteins[20].

8.1Fibrous proteins¶

Fibrous proteins are a class of proteins characterized by their elongated, fiber-like shapes. Their primary role is to provide mechanical support, strength, and elasticity to cells and tissues. Fibrous proteins are typically very large and form huge aggregates, making them insoluble in water. Their primary structure often contains repetitive sequences that facilitate the formation of regular secondary structures and the interactions between adjacent chains which lead to the formation of higher-order aggregates (quaternary structures in protein lingo). These proteins are essential for maintaining structural integrity, protecting tissues, allowing flexibility, and playing a crucial role in tissue repair and wound healing.

8.1.1-structural proteins¶

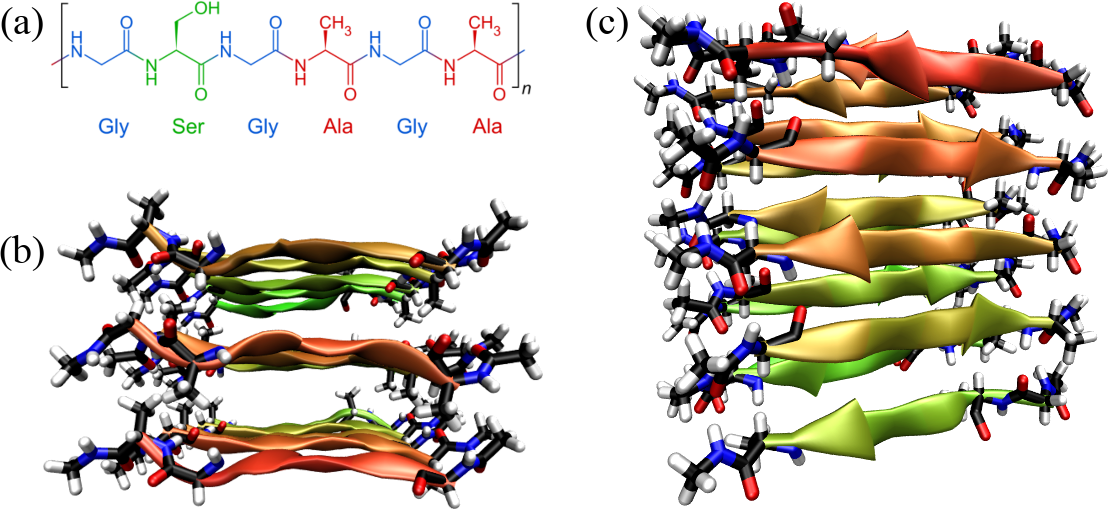

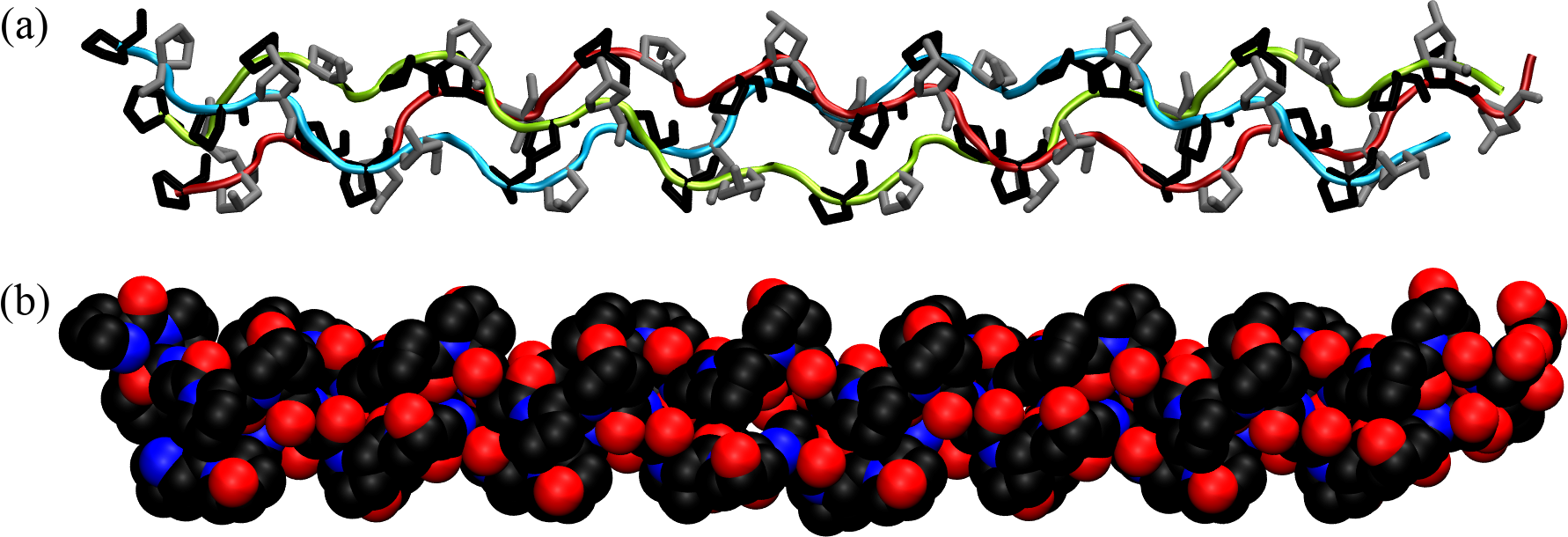

Figure 18:Silk fibroin: its primary structure (a) (credits to Sponk via Wikipedia Commons), and a fragment of model silk fibroin[22] as seen from the top (b) and from the side (c).

Figure 18 shows the primary and tertiary structure[22] of a representative of -structural proteins: silk fibroin. Silk fibroin is a fibrous protein produced by spiders and silkworms. Silk fibroin consists of repetitive sequences rich in glycine, alanine, and serine: a six-residue block like the one shown in the figure, where Gly alternates with larger residues, is repeated 8 times. These octads are repeated tens of times, interspersed by less regular sequences. The mostly small amino acids of the sequence facilitate tight packing and formation of -sheets, forming extensive hydrogen-bonded networks that contribute to the material’s strength and stability. In turn, as shown in the figure, the -sheets are stacked together, leading to highly ordered, quasi-crystalline regions that are interspersed with less ordered amorphous regions. Those are formed by irregular parts of the fibroin itself, as well as by the disordered matrix protein sericin.

8.1.2-structural proteins¶

(a)The crystal structure of interacting regions from the central coiled-coil domains of keratins 5 and 14. Side chains are shown with the licorice representation, while sulfur atoms are shown as yellow van der Waals spheres.

(b)Schematics showing the left-handedness of the coiled coil, the "knobs into holes" packing, and the interactions between residues belonging to the two helices.

Figure 19:Coiled coils. Figure 19a has been generated by using the structure solved in (Lee et al. (2012)), while Figure 19b has been adapted from Lapenta et al. (2018).

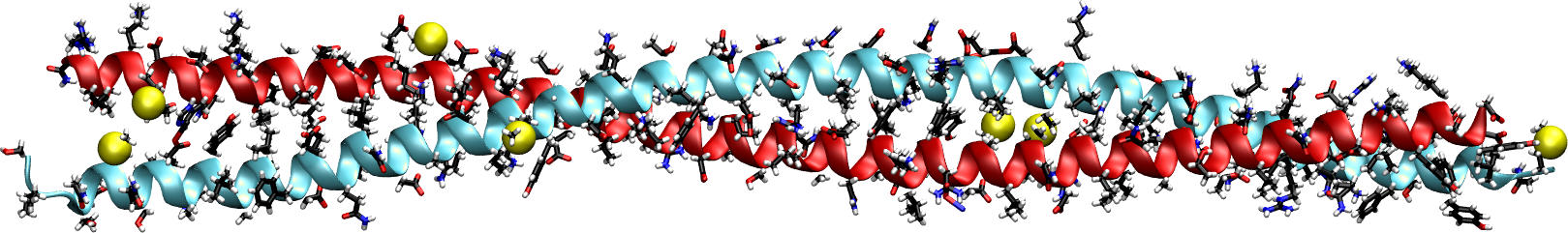

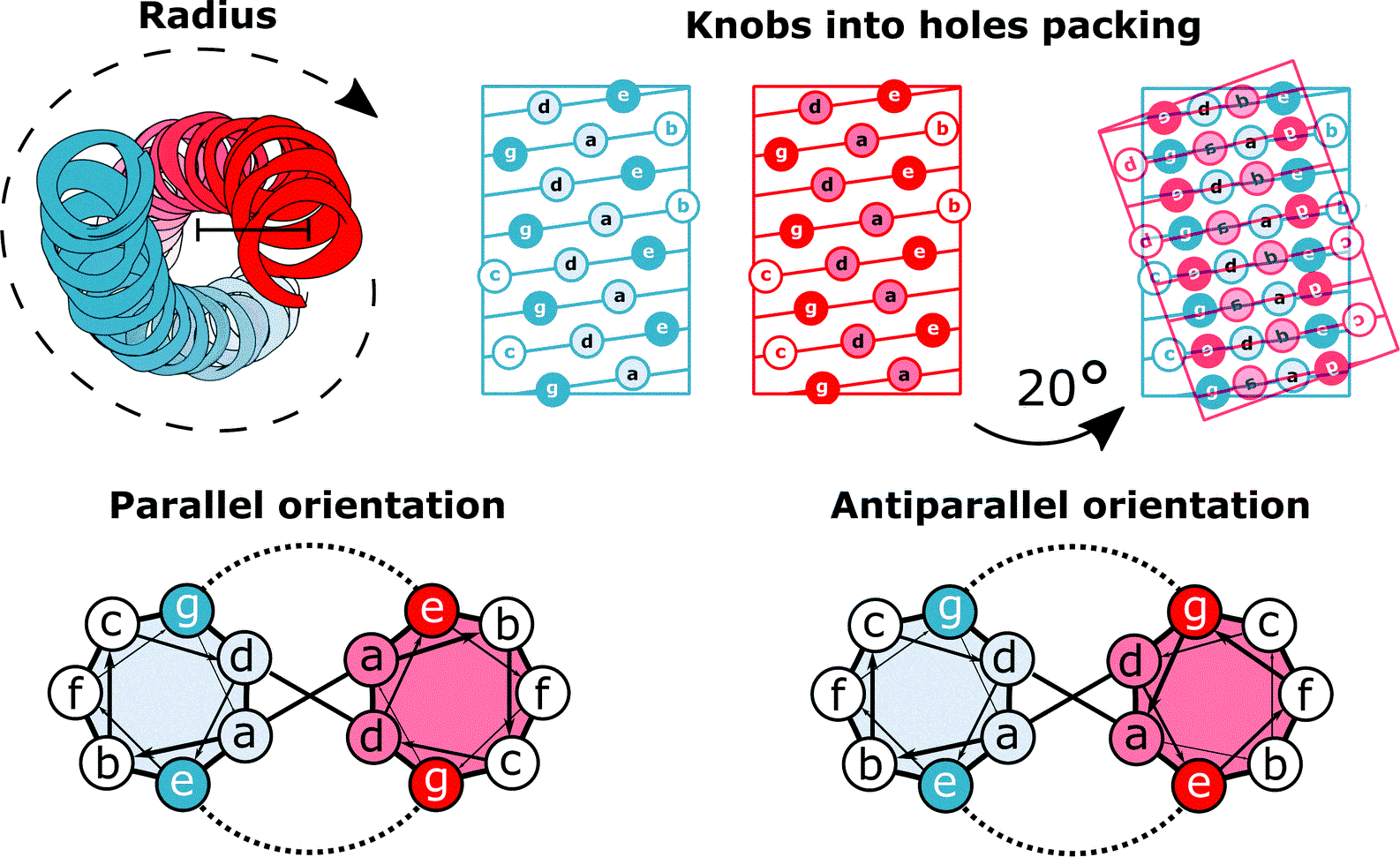

A typical example of -structural fibrous proteins is keratin, a protein crucial for the structural integrity and protection of vertebrate tissues, including hair, nails, feathers, horns, and skin. Composed primarily of amino acids with a high cysteine content, keratin forms -helices that assemble into left-handed supercoiled helices called “coiled coils”.

Figure 19a shows a part of the coiled coil generated by interacting regions of two proteins that compose keratin. As illustrated in Figure 19b, the primary structure of proteins forming coiled coils is characterized by a specific repeating pattern of amino acids, known as a heptad repeat. This repeating sequence consists of seven amino acids, denoted as (a-b-c-d-e-f-g), where positions a and d are typically occupied by hydrophobic residues (such as leucine, isoleucine, valine, or methionine) that interact with each other in the core of the coiled coil, stabilizing the structure through hydrophobic interactions. Indeed, when one of the helix is rotated by , the side chains of amino acids at the a and d positions in one -helix (the “knobs”) project outward from the helix and fit into the spaces (“holes”) formed by the side chains of the neighboring helices.

In some cases coiled coils further assemble into durable fibrils reinforced by disulfide bonds provided by cysteine residues (identified by the sulfur atoms shown as yellow van der Waals spheres in Figure 19a). This structure gives keratin its strength, rigidity, and insolubility, making it resistant to environmental stress.

8.1.3Collagen¶

Collagen is a major component of the extracellular matrix in various connective tissues of animals. It is one of the most abundant proteins in vertebrates, making up about a quarter of their total protein mass. Collagen provides structural support, strength, and elasticity to tissues such as skin, tendons, ligaments, cartilage, bones, and blood vessels.

Figure 20:The collagen triple helix or tropocollagen, taken from here. In (a) the backbones of the three chains are shown with ribbons of different colours, while prolines and hydroxyprolines are shown in black and silver, respectively. (b) shows the same configuration with atoms as van der Waals spheres.

The primary structure of collagen consists of a repeating tripeptide sequence Gly-X-Y, where X is often proline, and Y is often hydroxyproline, which is a post-translational modification of proline.

Each polypeptide chain containing the repeating sequence forms a left-handed helix with 3 residues per turn, which is stabilized by the kinks induced by the pyrrolidine rings of proline and hydroxyproline residues. However, the single helix does not form any hydrogen bonds and therefore it is not stable in isolation. In turn, as shown in Figure 20, three helices can wind around each other in a right-handed fashion to form a superhelix (the tropocollagen molecule), stabilised by HBs formed by the Gly residues[23]. Moreover, the three chains are closely packed together, and the interior of the triple helix is very small and hydrophobic, requiring every third residue of the helix to interact with this central region. As a result, only the small hydrogen atom of glycine’s side chain can fit and make contact with the center: any substitution of Gly with a larger amino acid can lead to distortions or disruptions in the triple helix, potentially leading to diseases such as osteogenesis imperfecta.

Triple helices, in turn, associate into higher order structures (collagen fibrils) that are held together by covalent cross-links catalysed by an enzyme that join together modified residues. Note that the process of collagen formation is not spontaneous but comprises many steps that require the cell machinery (see Finkelstein & Ptitsyn (2002) and references therein).

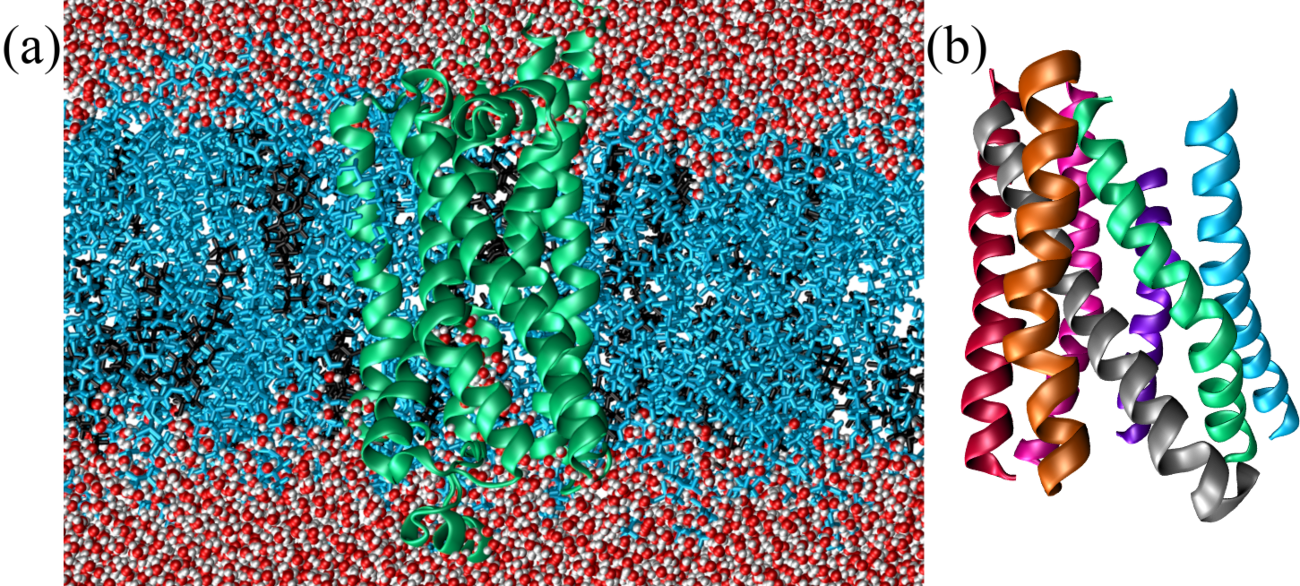

8.2Membrane proteins¶

Biological membranes are thin, flexible structures that form the boundaries of cells and organelles (which are cell compartments), regulating the movement of substances in and out. They play crucial roles in cellular communication, energy transduction, and maintaining homeostasis. Membranes are composed of

lipid bilayers, which consist of two layers of phospholipids with hydrophilic heads facing outward and hydrophobic tails facing inward, creating an insulating barrier;

membrane proteins, which are embedded within or associated with the lipid bilayer, acting as conductors, facilitating the selective transport of molecules across the membrane and transmitting signals between the cell’s internal and external environments.

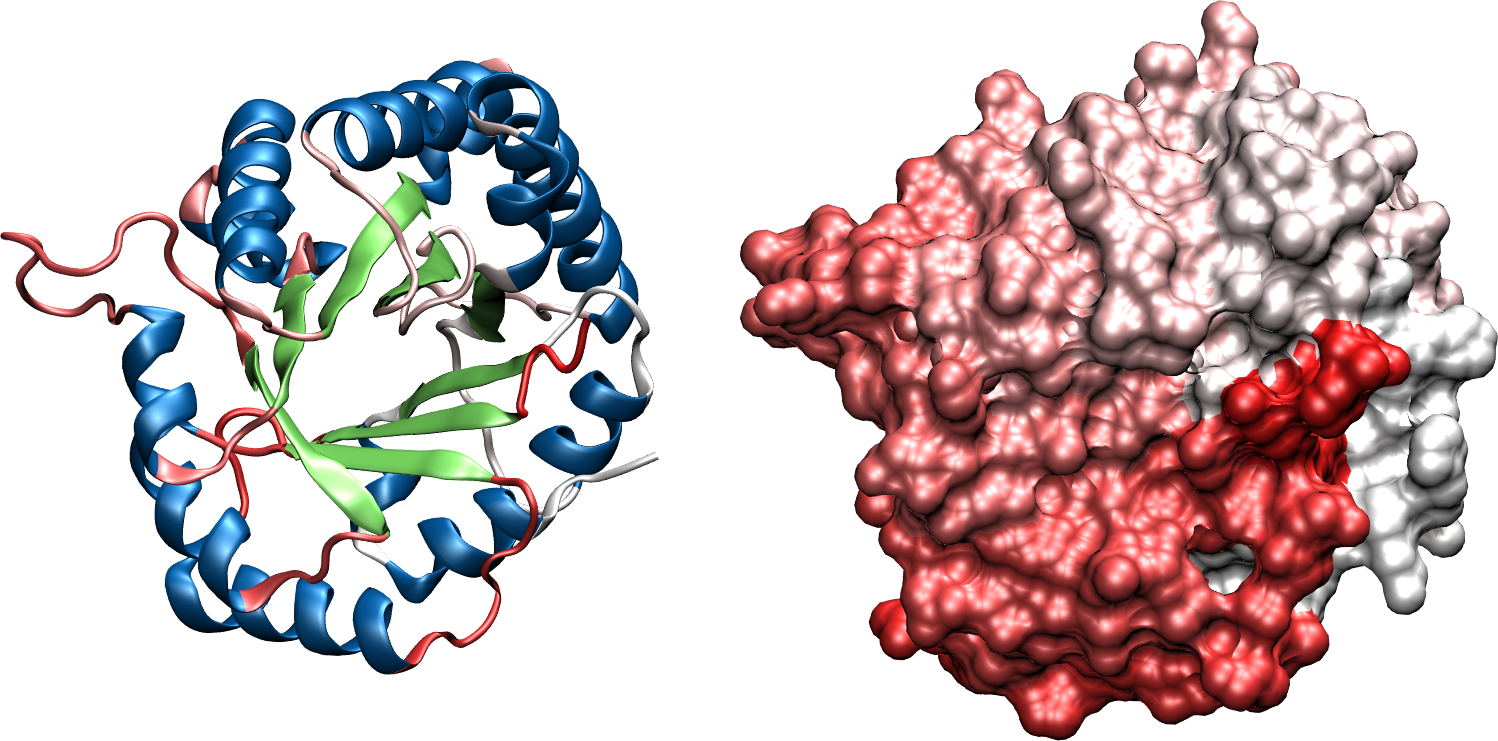

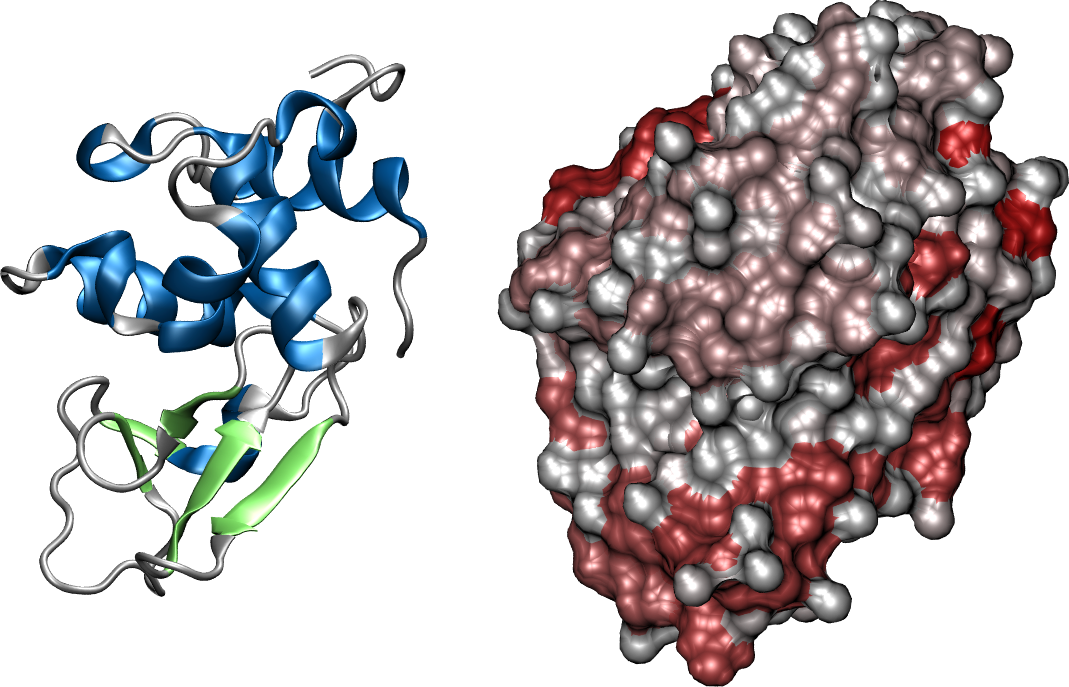

Membrane proteins are further classified in integral and peripheral proteins: integral membrane proteins are embedded within the lipid bilayer, often spanning it multiple times, while peripheral membrane proteins are attached to the membrane surface.